2014

Exibindo questões de 101 a 200.

Segundo o texto, um papel fundamental da religião, na - VUNESP 2014

Literatura - 2014Leia o texto para responder à questão.

A partir do século VII a.C., muitas comunidades nas ilhas, na Grécia continental, nas costas da Turquia e na Itália construíram grandes templos destinados a deuses específicos: os deuses de cada cidade.

As construções de templos foram verdadeiramente monumentais. [...] Tornaram-se as novas moradias dos deuses. Não eram mais deuses de uma família aristocráti- ca ou de uma etnia, mas de uma pólis. Eram os deuses da comunidade como um todo. A religião surgiu, assim, como um fator aglutinador das forças cooperativas da pólis. [...]

A construção monumental foi influenciada por mode- los egípcios e orientais. Sem as proezas de cálculo ma- temático, desenvolvidas na Mesopotâmia e no Egito, os grandes monumentos gregos teriam sido impossíveis.

Ao empregar a expressão “sprint”, o autor do texto - VUNESP 2014

Língua Portuguesa - 2014A questão abordam um texto de um site especializado em esportes com instruções de treinamento para a corrida olímpica dos 1 500 metros.

Corrida - Prova 1 500 metros rasos

A prova dos 1 500 metros rasos, juntamente com a da milha (1 609 metros), característica dos países anglo-saxônicos, é considerada prova tática por excelência, sendo muito importante o conhecimento do ritmo e da fórmula a ser utilizada para vencer a prova. Os especialistas nessas distâncias são considerados completos homens de luta que, após um penoso esforço para resistir ao ataque dos adversários, recorrem a todas as suas energias restantes a fim de manter a posição de destaque conseguida durante a corrida, sem ceder ao constante assédio dos seus perseguidores.

[...] Para correr essa distância em um tempo aceitável, deve-se gastar o menor tempo possível no primeiro quarto da prova, devendo-se para tanto sair na frente dos adversários, sendo essencial o completo domínio das pernas, para em seguida normalizar o ritmo da corrida. No segundo quarto, deve-se diminuir o ritmo, a fim de trabalhar forte no restante da prova, sempre procurando dosar as energias, para não correr o risco de ser surpreendido por um adversário e ficar sem condições para a luta final.

Deve ser tomado cuidado para não se deixar enganar por algum adversário de condição inferior, que normalmente finge possuir energias que realmente não tem, com o intuito de minar o bom corredor, para que o companheiro da mesma equipe possa tirar proveito da situação e vencer a prova. Assim sendo, o corredor experiente saberá manter regularmente as suas passadas, sem deixar-se levar por esse tipo de artimanha. Conhecendo o estado de suas condições pessoais, o corredor saberá se é capaz de um sprint nos 200 metros finais, que é a distância ideal para quebrar a resistência de um adversário pouco experiente.

O corredor que possui resistência e velocidade pode conduzir a corrida segundo a sua conveniência, impondo os seus próprios meios de ação. Finalmente, ao ultrapassar um adversário, deve-se fazê-lo decidida e folgadamente, procurando sempre impressioná-lo com sua ação enérgica. Também deve-se procurar manter sempre uma boa descontração muscular durante o desenvolvimento da corrida, nunca levar a cabeça para trás e encurtar as passadas para finalizar a prova.

(http://treino-de-corrida.f1cf.com.br)

A questão abordam um texto de um site especializado em - VUNESP 2014

Língua Portuguesa - 2014A questão abordam um texto de um site especializado em esportes com instruções de treinamento para a corrida olímpica dos 1 500 metros.

Corrida - Prova 1 500 metros rasos

A prova dos 1 500 metros rasos, juntamente com a da milha (1 609 metros), característica dos países anglo-saxônicos, é considerada prova tática por excelência, sendo muito importante o conhecimento do ritmo e da fórmula a ser utilizada para vencer a prova. Os especialistas nessas distâncias são considerados completos homens de luta que, após um penoso esforço para resistir ao ataque dos adversários, recorrem a todas as suas energias restantes a fim de manter a posição de destaque conseguida durante a corrida, sem ceder ao constante assédio dos seus perseguidores.

[...] Para correr essa distância em um tempo aceitável, deve-se gastar o menor tempo possível no primeiro quarto da prova, devendo-se para tanto sair na frente dos adversários, sendo essencial o completo domínio das pernas, para em seguida normalizar o ritmo da corrida. No segundo quarto, deve-se diminuir o ritmo, a fim de trabalhar forte no restante da prova, sempre procurando dosar as energias, para não correr o risco de ser surpreendido por um adversário e ficar sem condições para a luta final.

Deve ser tomado cuidado para não se deixar enganar por algum adversário de condição inferior, que normalmente finge possuir energias que realmente não tem, com o intuito de minar o bom corredor, para que o companheiro da mesma equipe possa tirar proveito da situação e vencer a prova. Assim sendo, o corredor experiente saberá manter regularmente as suas passadas, sem deixar-se levar por esse tipo de artimanha. Conhecendo o estado de suas condições pessoais, o corredor saberá se é capaz de um sprint nos 200 metros finais, que é a distância ideal para quebrar a resistência de um adversário pouco experiente.

O corredor que possui resistência e velocidade pode conduzir a corrida segundo a sua conveniência, impondo os seus próprios meios de ação. Finalmente, ao ultrapassar um adversário, deve-se fazê-lo decidida e folgadamente, procurando sempre impressioná-lo com sua ação enérgica. Também deve-se procurar manter sempre uma boa descontração muscular durante o desenvolvimento da corrida, nunca levar a cabeça para trás e encurtar as passadas para finalizar a prova.

(http://treino-de-corrida.f1cf.com.br)

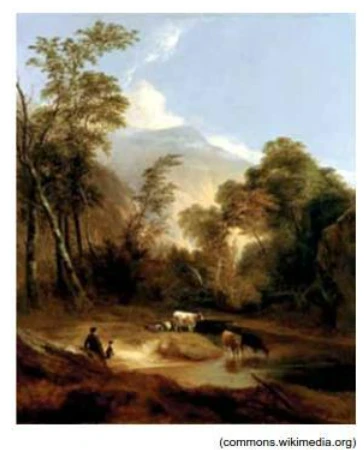

Examine a tela do pintor Alvan Fisher (1792-1863). - VUNESP 2014

Língua Portuguesa - 2014Examine a tela do pintor Alvan Fisher (1792-1863).

Pela própria descrição da corrida no texto, verifica-se - VUNESP 2014

Língua Portuguesa - 2014A questão abordam um texto de um site especializado em esportes com instruções de treinamento para a corrida olímpica dos 1 500 metros.

Corrida - Prova 1 500 metros rasos

A prova dos 1 500 metros rasos, juntamente com a da milha (1 609 metros), característica dos países anglo-saxônicos, é considerada prova tática por excelência, sendo muito importante o conhecimento do ritmo e da fórmula a ser utilizada para vencer a prova. Os especialistas nessas distâncias são considerados completos homens de luta que, após um penoso esforço para resistir ao ataque dos adversários, recorrem a todas as suas energias restantes a fim de manter a posição de destaque conseguida durante a corrida, sem ceder ao constante assédio dos seus perseguidores.

[...] Para correr essa distância em um tempo aceitável, deve-se gastar o menor tempo possível no primeiro quarto da prova, devendo-se para tanto sair na frente dos adversários, sendo essencial o completo domínio das pernas, para em seguida normalizar o ritmo da corrida. No segundo quarto, deve-se diminuir o ritmo, a fim de trabalhar forte no restante da prova, sempre procurando dosar as energias, para não correr o risco de ser surpreendido por um adversário e ficar sem condições para a luta final.

Deve ser tomado cuidado para não se deixar enganar por algum adversário de condição inferior, que normalmente finge possuir energias que realmente não tem, com o intuito de minar o bom corredor, para que o companheiro da mesma equipe possa tirar proveito da situação e vencer a prova. Assim sendo, o corredor experiente saberá manter regularmente as suas passadas, sem deixar-se levar por esse tipo de artimanha. Conhecendo o estado de suas condições pessoais, o corredor saberá se é capaz de um sprint nos 200 metros finais, que é a distância ideal para quebrar a resistência de um adversário pouco experiente.

O corredor que possui resistência e velocidade pode conduzir a corrida segundo a sua conveniência, impondo os seus próprios meios de ação. Finalmente, ao ultrapassar um adversário, deve-se fazê-lo decidida e folgadamente, procurando sempre impressioná-lo com sua ação enérgica. Também deve-se procurar manter sempre uma boa descontração muscular durante o desenvolvimento da corrida, nunca levar a cabeça para trás e encurtar as passadas para finalizar a prova.

(http://treino-de-corrida.f1cf.com.br)

No terceiro parágrafo, descreve-se uma “artimanha” nessa - VUNESP 2014

Língua Portuguesa - 2014A questão abordam um texto de um site especializado em esportes com instruções de treinamento para a corrida olímpica dos 1 500 metros.

Corrida - Prova 1 500 metros rasos

A prova dos 1 500 metros rasos, juntamente com a da milha (1 609 metros), característica dos países anglo-saxônicos, é considerada prova tática por excelência, sendo muito importante o conhecimento do ritmo e da fórmula a ser utilizada para vencer a prova. Os especialistas nessas distâncias são considerados completos homens de luta que, após um penoso esforço para resistir ao ataque dos adversários, recorrem a todas as suas energias restantes a fim de manter a posição de destaque conseguida durante a corrida, sem ceder ao constante assédio dos seus perseguidores.

[...] Para correr essa distância em um tempo aceitável, deve-se gastar o menor tempo possível no primeiro quarto da prova, devendo-se para tanto sair na frente dos adversários, sendo essencial o completo domínio das pernas, para em seguida normalizar o ritmo da corrida. No segundo quarto, deve-se diminuir o ritmo, a fim de trabalhar forte no restante da prova, sempre procurando dosar as energias, para não correr o risco de ser surpreendido por um adversário e ficar sem condições para a luta final.

Deve ser tomado cuidado para não se deixar enganar por algum adversário de condição inferior, que normalmente finge possuir energias que realmente não tem, com o intuito de minar o bom corredor, para que o companheiro da mesma equipe possa tirar proveito da situação e vencer a prova. Assim sendo, o corredor experiente saberá manter regularmente as suas passadas, sem deixar-se levar por esse tipo de artimanha. Conhecendo o estado de suas condições pessoais, o corredor saberá se é capaz de um sprint nos 200 metros finais, que é a distância ideal para quebrar a resistência de um adversário pouco experiente.

O corredor que possui resistência e velocidade pode conduzir a corrida segundo a sua conveniência, impondo os seus próprios meios de ação. Finalmente, ao ultrapassar um adversário, deve-se fazê-lo decidida e folgadamente, procurando sempre impressioná-lo com sua ação enérgica. Também deve-se procurar manter sempre uma boa descontração muscular durante o desenvolvimento da corrida, nunca levar a cabeça para trás e encurtar as passadas para finalizar a prova.

(http://treino-de-corrida.f1cf.com.br)

Segundo o texto, antes desse tipo de corrida, é muito - VUNESP 2014

Língua Portuguesa - 2014A questão abordam um texto de um site especializado em esportes com instruções de treinamento para a corrida olímpica dos 1 500 metros.

Corrida - Prova 1 500 metros rasos

A prova dos 1 500 metros rasos, juntamente com a da milha (1 609 metros), característica dos países anglo-saxônicos, é considerada prova tática por excelência, sendo muito importante o conhecimento do ritmo e da fórmula a ser utilizada para vencer a prova. Os especialistas nessas distâncias são considerados completos homens de luta que, após um penoso esforço para resistir ao ataque dos adversários, recorrem a todas as suas energias restantes a fim de manter a posição de destaque conseguida durante a corrida, sem ceder ao constante assédio dos seus perseguidores.

[...] Para correr essa distância em um tempo aceitável, deve-se gastar o menor tempo possível no primeiro quarto da prova, devendo-se para tanto sair na frente dos adversários, sendo essencial o completo domínio das pernas, para em seguida normalizar o ritmo da corrida. No segundo quarto, deve-se diminuir o ritmo, a fim de trabalhar forte no restante da prova, sempre procurando dosar as energias, para não correr o risco de ser surpreendido por um adversário e ficar sem condições para a luta final.

Deve ser tomado cuidado para não se deixar enganar por algum adversário de condição inferior, que normalmente finge possuir energias que realmente não tem, com o intuito de minar o bom corredor, para que o companheiro da mesma equipe possa tirar proveito da situação e vencer a prova. Assim sendo, o corredor experiente saberá manter regularmente as suas passadas, sem deixar-se levar por esse tipo de artimanha. Conhecendo o estado de suas condições pessoais, o corredor saberá se é capaz de um sprint nos 200 metros finais, que é a distância ideal para quebrar a resistência de um adversário pouco experiente.

O corredor que possui resistência e velocidade pode conduzir a corrida segundo a sua conveniência, impondo os seus próprios meios de ação. Finalmente, ao ultrapassar um adversário, deve-se fazê-lo decidida e folgadamente, procurando sempre impressioná-lo com sua ação enérgica. Também deve-se procurar manter sempre uma boa descontração muscular durante o desenvolvimento da corrida, nunca levar a cabeça para trás e encurtar as passadas para finalizar a prova.

(http://treino-de-corrida.f1cf.com.br)

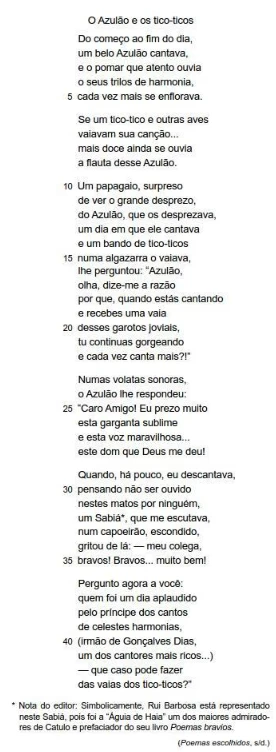

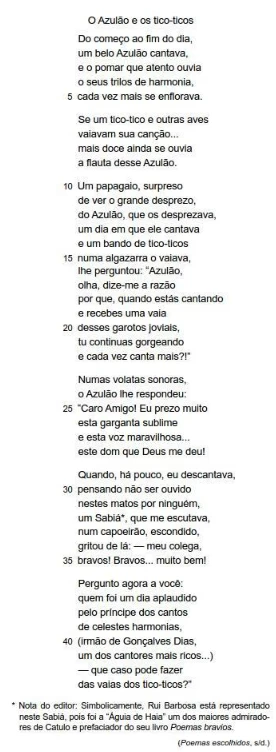

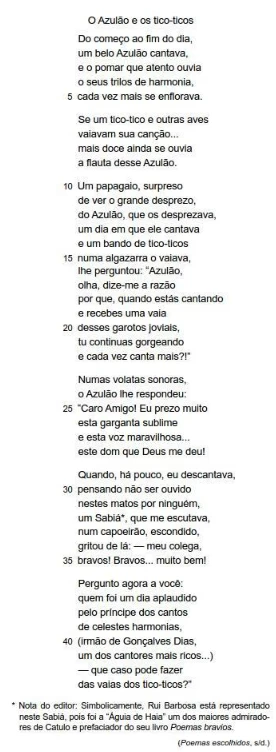

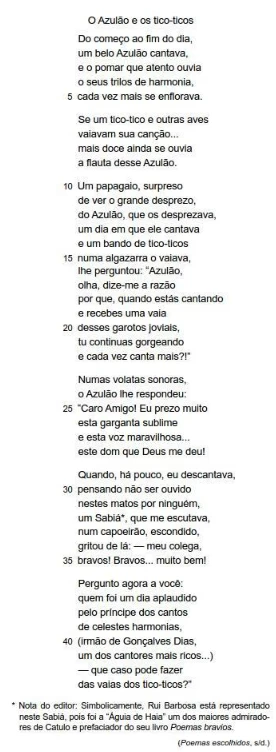

E, nos versos 32 e 33, as palavras “Sabiá” e “capoeirão" - VUNESP 2014

Língua Portuguesa - 2014Para responder à questão, leia o poema de Catulo da Paixão Cearense (1863-1946).

Considerando a nota do editor, que identifica o Sabiá - VUNESP 2014

Língua Portuguesa - 2014Para responder à questão, leia o poema de Catulo da Paixão Cearense (1863-1946).

Na fala do papagaio, dos versos de números 16 a 22, uma - VUNESP 2014

Língua Portuguesa - 2014Para responder à questão, leia o poema de Catulo da Paixão Cearense (1863-1946).

Ante as vaias dos tico-ticos e outras aves, o Azulão - VUNESP 2014

Língua Portuguesa - 2014Para responder à questão, leia o poema de Catulo da Paixão Cearense (1863-1946).

Tomando por base a leitura do poema, verifica-se que o - VUNESP 2014

Língua Portuguesa - 2014Para responder à questão, leia o poema de Catulo da Paixão Cearense (1863-1946).

No último parágrafo, focalizando o mercado de trabalho - VUNESP 2014

Língua Portuguesa - 2014A questão focaliza uma passagem de um artigo de Cláudia Vassallo.

Aliadas ou concorrentes

Alguns números: nos Estados Unidos, 60% dos formados em universidades são mulheres. Metade das europeias que estão no mercado de trabalho passou por universidades. No Japão, as mulheres têm níveis semelhantes de educação, mas deixam o mercado assim que se casam e têm filhos. A tradição joga contra a economia. O governo credita parte da estagnação dos últimos anos à ausência de participação feminina no mercado de trabalho. As brasileiras avançam mais rápido na educação. Atualmente, 12% das mulheres têm diploma universitário - ante 10% dos homens. Metade das garotas de 15 entrevistadas numa pesquisa da OCDE1 disse pretender fazer carreira em engenharia e ciências - áreas especialmente promissoras.

[...]

Agora, a condição de minoria vai caindo por terra e os padrões de comportamento começam a mudar. Cada vez menos mulheres estão dispostas a abdicar de sua natureza em nome da carreira. Não se trata de mudar a essência do trabalho e das obrigações que homens e mulheres têm de encarar. Não se trata de trabalhar menos ou ter menos ambição. É só uma questão de forma. É muito provável que legisladores e empresas tenham de ser mais flexíveis para abrigar mulheres de talento que não desistiram do papel de mãe. Porque, de fato, essa é a grande e única questão de gênero que importa.

Mais fortalecidas e mais preparadas, as mulheres terão um lugar ao sol nas empresas do jeito que são ou desistirão delas, porque serão capazes de ganhar dinheiro de outra forma. Há 8,3 milhões de empresas lideradas por mulheres nos Estados Unidos - é o tipo de empreendedorismo que mais cresce no país. De acordo com um estudo da EY2 , o Brasil tem 10,4 milhões de empreendedoras, o maior índice entre as 20 maiores economias. Um número crescente delas tem migrado das grandes empresas para o próprio negócio. Os fatos mostram: as empresas em todo o mundo terão, mais cedo ou mais tarde, de decidir se querem ter metade da população como aliada ou como concorrente.

(Exame, outubro de 2013.)

¹OCDE: Organização para a Cooperação e Desenvolvimento Econômico.

² EY: Organização global com o objetivo de auxiliar seus clientes a fortalecerem seus negócios ao redor do mundo.

Desde o título do artigo, que é retomado no último - VUNESP 2014

Língua Portuguesa - 2014A questão focaliza uma passagem de um artigo de Cláudia Vassallo.

Aliadas ou concorrentes

Alguns números: nos Estados Unidos, 60% dos formados em universidades são mulheres. Metade das europeias que estão no mercado de trabalho passou por universidades. No Japão, as mulheres têm níveis semelhantes de educação, mas deixam o mercado assim que se casam e têm filhos. A tradição joga contra a economia. O governo credita parte da estagnação dos últimos anos à ausência de participação feminina no mercado de trabalho. As brasileiras avançam mais rápido na educação. Atualmente, 12% das mulheres têm diploma universitário - ante 10% dos homens. Metade das garotas de 15 entrevistadas numa pesquisa da OCDE1 disse pretender fazer carreira em engenharia e ciências - áreas especialmente promissoras.

[...]

Agora, a condição de minoria vai caindo por terra e os padrões de comportamento começam a mudar. Cada vez menos mulheres estão dispostas a abdicar de sua natureza em nome da carreira. Não se trata de mudar a essência do trabalho e das obrigações que homens e mulheres têm de encarar. Não se trata de trabalhar menos ou ter menos ambição. É só uma questão de forma. É muito provável que legisladores e empresas tenham de ser mais flexíveis para abrigar mulheres de talento que não desistiram do papel de mãe. Porque, de fato, essa é a grande e única questão de gênero que importa.

Mais fortalecidas e mais preparadas, as mulheres terão um lugar ao sol nas empresas do jeito que são ou desistirão delas, porque serão capazes de ganhar dinheiro de outra forma. Há 8,3 milhões de empresas lideradas por mulheres nos Estados Unidos - é o tipo de empreendedorismo que mais cresce no país. De acordo com um estudo da EY2 , o Brasil tem 10,4 milhões de empreendedoras, o maior índice entre as 20 maiores economias. Um número crescente delas tem migrado das grandes empresas para o próprio negócio. Os fatos mostram: as empresas em todo o mundo terão, mais cedo ou mais tarde, de decidir se querem ter metade da população como aliada ou como concorrente.

(Exame, outubro de 2013.)

¹OCDE: Organização para a Cooperação e Desenvolvimento Econômico.

² EY: Organização global com o objetivo de auxiliar seus clientes a fortalecerem seus negócios ao redor do mundo.

Em sua argumentação, a autora revela que a importância - VUNESP 2014

Língua Portuguesa - 2014A questão focaliza uma passagem de um artigo de Cláudia Vassallo.

Aliadas ou concorrentes

Alguns números: nos Estados Unidos, 60% dos formados em universidades são mulheres. Metade das europeias que estão no mercado de trabalho passou por universidades. No Japão, as mulheres têm níveis semelhantes de educação, mas deixam o mercado assim que se casam e têm filhos. A tradição joga contra a economia. O governo credita parte da estagnação dos últimos anos à ausência de participação feminina no mercado de trabalho. As brasileiras avançam mais rápido na educação. Atualmente, 12% das mulheres têm diploma universitário - ante 10% dos homens. Metade das garotas de 15 entrevistadas numa pesquisa da OCDE1 disse pretender fazer carreira em engenharia e ciências - áreas especialmente promissoras.

[...]

Agora, a condição de minoria vai caindo por terra e os padrões de comportamento começam a mudar. Cada vez menos mulheres estão dispostas a abdicar de sua natureza em nome da carreira. Não se trata de mudar a essência do trabalho e das obrigações que homens e mulheres têm de encarar. Não se trata de trabalhar menos ou ter menos ambição. É só uma questão de forma. É muito provável que legisladores e empresas tenham de ser mais flexíveis para abrigar mulheres de talento que não desistiram do papel de mãe. Porque, de fato, essa é a grande e única questão de gênero que importa.

Mais fortalecidas e mais preparadas, as mulheres terão um lugar ao sol nas empresas do jeito que são ou desistirão delas, porque serão capazes de ganhar dinheiro de outra forma. Há 8,3 milhões de empresas lideradas por mulheres nos Estados Unidos - é o tipo de empreendedorismo que mais cresce no país. De acordo com um estudo da EY2 , o Brasil tem 10,4 milhões de empreendedoras, o maior índice entre as 20 maiores economias. Um número crescente delas tem migrado das grandes empresas para o próprio negócio. Os fatos mostram: as empresas em todo o mundo terão, mais cedo ou mais tarde, de decidir se querem ter metade da população como aliada ou como concorrente.

(Exame, outubro de 2013.)

¹OCDE: Organização para a Cooperação e Desenvolvimento Econômico.

² EY: Organização global com o objetivo de auxiliar seus clientes a fortalecerem seus negócios ao redor do mundo.

“Cada vez menos mulheres estão dispostas a abdicar de - VUNESP 2014

Língua Portuguesa - 2014A questão focaliza uma passagem de um artigo de Cláudia Vassallo.

Aliadas ou concorrentes

Alguns números: nos Estados Unidos, 60% dos formados em universidades são mulheres. Metade das europeias que estão no mercado de trabalho passou por universidades. No Japão, as mulheres têm níveis semelhantes de educação, mas deixam o mercado assim que se casam e têm filhos. A tradição joga contra a economia. O governo credita parte da estagnação dos últimos anos à ausência de participação feminina no mercado de trabalho. As brasileiras avançam mais rápido na educação. Atualmente, 12% das mulheres têm diploma universitário - ante 10% dos homens. Metade das garotas de 15 entrevistadas numa pesquisa da OCDE1 disse pretender fazer carreira em engenharia e ciências - áreas especialmente promissoras.

[...]

Agora, a condição de minoria vai caindo por terra e os padrões de comportamento começam a mudar. Cada vez menos mulheres estão dispostas a abdicar de sua natureza em nome da carreira. Não se trata de mudar a essência do trabalho e das obrigações que homens e mulheres têm de encarar. Não se trata de trabalhar menos ou ter menos ambição. É só uma questão de forma. É muito provável que legisladores e empresas tenham de ser mais flexíveis para abrigar mulheres de talento que não desistiram do papel de mãe. Porque, de fato, essa é a grande e única questão de gênero que importa.

Mais fortalecidas e mais preparadas, as mulheres terão um lugar ao sol nas empresas do jeito que são ou desistirão delas, porque serão capazes de ganhar dinheiro de outra forma. Há 8,3 milhões de empresas lideradas por mulheres nos Estados Unidos - é o tipo de empreendedorismo que mais cresce no país. De acordo com um estudo da EY2 , o Brasil tem 10,4 milhões de empreendedoras, o maior índice entre as 20 maiores economias. Um número crescente delas tem migrado das grandes empresas para o próprio negócio. Os fatos mostram: as empresas em todo o mundo terão, mais cedo ou mais tarde, de decidir se querem ter metade da população como aliada ou como concorrente.

(Exame, outubro de 2013.)

¹OCDE: Organização para a Cooperação e Desenvolvimento Econômico.

² EY: Organização global com o objetivo de auxiliar seus clientes a fortalecerem seus negócios ao redor do mundo.

Indique a acepção da palavra “estagnação” que melhor se - VUNESP 2014

Língua Portuguesa - 2014A questão focaliza uma passagem de um artigo de Cláudia Vassallo.

Aliadas ou concorrentes

Alguns números: nos Estados Unidos, 60% dos formados em universidades são mulheres. Metade das europeias que estão no mercado de trabalho passou por universidades. No Japão, as mulheres têm níveis semelhantes de educação, mas deixam o mercado assim que se casam e têm filhos. A tradição joga contra a economia. O governo credita parte da estagnação dos últimos anos à ausência de participação feminina no mercado de trabalho. As brasileiras avançam mais rápido na educação. Atualmente, 12% das mulheres têm diploma universitário - ante 10% dos homens. Metade das garotas de 15 entrevistadas numa pesquisa da OCDE1 disse pretender fazer carreira em engenharia e ciências - áreas especialmente promissoras.

[...]

Agora, a condição de minoria vai caindo por terra e os padrões de comportamento começam a mudar. Cada vez menos mulheres estão dispostas a abdicar de sua natureza em nome da carreira. Não se trata de mudar a essência do trabalho e das obrigações que homens e mulheres têm de encarar. Não se trata de trabalhar menos ou ter menos ambição. É só uma questão de forma. É muito provável que legisladores e empresas tenham de ser mais flexíveis para abrigar mulheres de talento que não desistiram do papel de mãe. Porque, de fato, essa é a grande e única questão de gênero que importa.

Mais fortalecidas e mais preparadas, as mulheres terão um lugar ao sol nas empresas do jeito que são ou desistirão delas, porque serão capazes de ganhar dinheiro de outra forma. Há 8,3 milhões de empresas lideradas por mulheres nos Estados Unidos - é o tipo de empreendedorismo que mais cresce no país. De acordo com um estudo da EY2 , o Brasil tem 10,4 milhões de empreendedoras, o maior índice entre as 20 maiores economias. Um número crescente delas tem migrado das grandes empresas para o próprio negócio. Os fatos mostram: as empresas em todo o mundo terão, mais cedo ou mais tarde, de decidir se querem ter metade da população como aliada ou como concorrente.

(Exame, outubro de 2013.)

¹OCDE: Organização para a Cooperação e Desenvolvimento Econômico.

² EY: Organização global com o objetivo de auxiliar seus clientes a fortalecerem seus negócios ao redor do mundo.

Analisando o último período do terceiro parágrafo, - VUNESP 2014

Língua Portuguesa - 2014A questão toma por base uma passagem de um romance de Autran Dourado (1926- 2012).

A gente Honório Cota

Quando o coronel João Capistrano Honório Cota mandou erguer o sobrado, tinha pouco mais de trinta anos. Mas já era homem sério de velho, reservado, cumpridor. Cuidava muito dos trajes, da sua aparência medida. O jaquetão de casimira inglesa, o colete de linho atravessado pela grossa corrente de ouro do relógio; a calça é que era como a de todos na cidade - de brim, a não ser em certas ocasiões (batizado, morte, casamento - então era parelho mesmo, por igual), mas sempre muito bem passada, o vinco perfeito. Dava gosto ver:

O passo vagaroso de quem não tem pressa - o mundo podia esperar por ele, o peito magro estufado, os gestos lentos, a voz pausada e grave, descia a rua da Igreja cumprimentando cerimoniosamente, nobremente, os que por ele passavam ou os que chegavam na janela muitas vezes só para vê-lo passar.

Desde longe a gente adivinhava ele vindo: alto, magro, descarnado, como uma ave pernalta de grande porte. Sendo assim tão descomunal, podia ser desajeitado: não era, dava sempre a impressão de uma grande e ponderada figura. Não jogava as pernas para os lados nem as trazia abertas, esticava-as feito medisse os passos, quebrando os joelhos em reto.

Quando montado, indo para a sua Fazenda da Pedra Menina, no cavalo branco ajaezado de couro trabalhado e prata, aí então sim era a grande, imponente figura, que enchia as vistas. Parecia um daqueles cavaleiros antigos, fugidos do Amadis de Gaula ou do Palmeirim, quando iam para a guerra armados cavaleiros.

No início do segundo parágrafo, por ter na frase a mesma - VUNESP 2014

Língua Portuguesa - 2014A questão toma por base uma passagem de um romance de Autran Dourado (1926- 2012).

A gente Honório Cota

Quando o coronel João Capistrano Honório Cota mandou erguer o sobrado, tinha pouco mais de trinta anos. Mas já era homem sério de velho, reservado, cumpridor. Cuidava muito dos trajes, da sua aparência medida. O jaquetão de casimira inglesa, o colete de linho atravessado pela grossa corrente de ouro do relógio; a calça é que era como a de todos na cidade - de brim, a não ser em certas ocasiões (batizado, morte, casamento - então era parelho mesmo, por igual), mas sempre muito bem passada, o vinco perfeito. Dava gosto ver:

O passo vagaroso de quem não tem pressa - o mundo podia esperar por ele, o peito magro estufado, os gestos lentos, a voz pausada e grave, descia a rua da Igreja cumprimentando cerimoniosamente, nobremente, os que por ele passavam ou os que chegavam na janela muitas vezes só para vê-lo passar.

Desde longe a gente adivinhava ele vindo: alto, magro, descarnado, como uma ave pernalta de grande porte. Sendo assim tão descomunal, podia ser desajeitado: não era, dava sempre a impressão de uma grande e ponderada figura. Não jogava as pernas para os lados nem as trazia abertas, esticava-as feito medisse os passos, quebrando os joelhos em reto.

Quando montado, indo para a sua Fazenda da Pedra Menina, no cavalo branco ajaezado de couro trabalhado e prata, aí então sim era a grande, imponente figura, que enchia as vistas. Parecia um daqueles cavaleiros antigos, fugidos do Amadis de Gaula ou do Palmeirim, quando iam para a guerra armados cavaleiros.

Em seu conjunto, a descrição do coronel sugere uma - VUNESP 2014

Língua Portuguesa - 2014A questão toma por base uma passagem de um romance de Autran Dourado (1926- 2012).

A gente Honório Cota

Quando o coronel João Capistrano Honório Cota mandou erguer o sobrado, tinha pouco mais de trinta anos. Mas já era homem sério de velho, reservado, cumpridor. Cuidava muito dos trajes, da sua aparência medida. O jaquetão de casimira inglesa, o colete de linho atravessado pela grossa corrente de ouro do relógio; a calça é que era como a de todos na cidade - de brim, a não ser em certas ocasiões (batizado, morte, casamento - então era parelho mesmo, por igual), mas sempre muito bem passada, o vinco perfeito. Dava gosto ver:

O passo vagaroso de quem não tem pressa - o mundo podia esperar por ele, o peito magro estufado, os gestos lentos, a voz pausada e grave, descia a rua da Igreja cumprimentando cerimoniosamente, nobremente, os que por ele passavam ou os que chegavam na janela muitas vezes só para vê-lo passar.

Desde longe a gente adivinhava ele vindo: alto, magro, descarnado, como uma ave pernalta de grande porte. Sendo assim tão descomunal, podia ser desajeitado: não era, dava sempre a impressão de uma grande e ponderada figura. Não jogava as pernas para os lados nem as trazia abertas, esticava-as feito medisse os passos, quebrando os joelhos em reto.

Quando montado, indo para a sua Fazenda da Pedra Menina, no cavalo branco ajaezado de couro trabalhado e prata, aí então sim era a grande, imponente figura, que enchia as vistas. Parecia um daqueles cavaleiros antigos, fugidos do Amadis de Gaula ou do Palmeirim, quando iam para a guerra armados cavaleiros.

No primeiro parágrafo, com a frase “então era parelho me - VUNESP 2013

Língua Portuguesa - 2014A questão toma por base uma passagem de um romance de Autran Dourado (1926- 2012).

A gente Honório Cota

Quando o coronel João Capistrano Honório Cota mandou erguer o sobrado, tinha pouco mais de trinta anos. Mas já era homem sério de velho, reservado, cumpridor. Cuidava muito dos trajes, da sua aparência medida. O jaquetão de casimira inglesa, o colete de linho atravessado pela grossa corrente de ouro do relógio; a calça é que era como a de todos na cidade - de brim, a não ser em certas ocasiões (batizado, morte, casamento - então era parelho mesmo, por igual), mas sempre muito bem passada, o vinco perfeito. Dava gosto ver:

O passo vagaroso de quem não tem pressa - o mundo podia esperar por ele, o peito magro estufado, os gestos lentos, a voz pausada e grave, descia a rua da Igreja cumprimentando cerimoniosamente, nobremente, os que por ele passavam ou os que chegavam na janela muitas vezes só para vê-lo passar.

Desde longe a gente adivinhava ele vindo: alto, magro, descarnado, como uma ave pernalta de grande porte. Sendo assim tão descomunal, podia ser desajeitado: não era, dava sempre a impressão de uma grande e ponderada figura. Não jogava as pernas para os lados nem as trazia abertas, esticava-as feito medisse os passos, quebrando os joelhos em reto.

Quando montado, indo para a sua Fazenda da Pedra Menina, no cavalo branco ajaezado de couro trabalhado e prata, aí então sim era a grande, imponente figura, que enchia as vistas. Parecia um daqueles cavaleiros antigos, fugidos do Amadis de Gaula ou do Palmeirim, quando iam para a guerra armados cavaleiros.

A questão toma por base uma passagem de um romance de - VUNESP 2014

Língua Portuguesa - 2014A questão toma por base uma passagem de um romance de Autran Dourado (1926- 2012).

A gente Honório Cota

Quando o coronel João Capistrano Honório Cota mandou erguer o sobrado, tinha pouco mais de trinta anos. Mas já era homem sério de velho, reservado, cumpridor. Cuidava muito dos trajes, da sua aparência medida. O jaquetão de casimira inglesa, o colete de linho atravessado pela grossa corrente de ouro do relógio; a calça é que era como a de todos na cidade - de brim, a não ser em certas ocasiões (batizado, morte, casamento - então era parelho mesmo, por igual), mas sempre muito bem passada, o vinco perfeito. Dava gosto ver:

O passo vagaroso de quem não tem pressa - o mundo podia esperar por ele, o peito magro estufado, os gestos lentos, a voz pausada e grave, descia a rua da Igreja cumprimentando cerimoniosamente, nobremente, os que por ele passavam ou os que chegavam na janela muitas vezes só para vê-lo passar.

Desde longe a gente adivinhava ele vindo: alto, magro, descarnado, como uma ave pernalta de grande porte. Sendo assim tão descomunal, podia ser desajeitado: não era, dava sempre a impressão de uma grande e ponderada figura. Não jogava as pernas para os lados nem as trazia abertas, esticava-as feito medisse os passos, quebrando os joelhos em reto.

Quando montado, indo para a sua Fazenda da Pedra Menina, no cavalo branco ajaezado de couro trabalhado e prata, aí então sim era a grande, imponente figura, que enchia as vistas. Parecia um daqueles cavaleiros antigos, fugidos do Amadis de Gaula ou do Palmeirim, quando iam para a guerra armados cavaleiros.

Estudos ambientais revelaram que o ferro é um dos metais - FGV 2015

Química - 2014Estudos ambientais revelaram que o ferro é um dos metais presentes em maior quantidade na atmosfera, apresentando-se na forma do íon de ferro 3+ hidratado, [Fe(H2O)6]3+. O íon de ferro na atmosfera se hidrolisa de acordo com a equação

[Fe(H2 O)6 ] 3+ ↔ [Fe(H2 O)5 OH]2+ + H+

O Brasil inaugurou em 2014 o Projeto Sirius, um acelerador - FGV 2015

Química - 2014O Brasil inaugurou em 2014 o Projeto Sirius, um acelerador de partículas que permitirá o desenvolvimento de pesquisa na área de materiais, física, química e biologia. Seu funcionamento se dará pelo fornecimento de energia a feixes de partículas subatômicas eletricamente carregadas: prótons e elétrons.

(http://www.brasil.gov.br/ciencia-e-tecnologia/2014/02/. Adaptado)

Na tabela, são apresentadas informações das quantidades de algumas partículas subatômicas para os íons X2– e A2+:

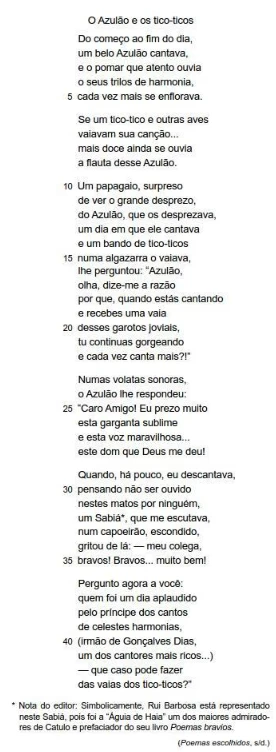

Um edifício comercial tem 48 salas, distribuídas em 8 - FGV 2015

Matemática - 2014Um edifício comercial tem 48 salas, distribuídas em 8 andares, conforme indica a figura. O edifício foi feito em um terreno cuja inclinação em relação à horizontal mede α graus. A altura de cada sala é 3 m, a extensão 10 m, e a altura da pilastra de sustentação, que mantém o edifício na horizontal, é 6 m.

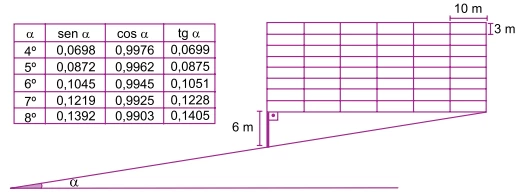

A figura representa um trapézio isósceles ABCD, com AD = BC - FGV 2015

Matemática - 2014A figura representa um trapézio isósceles ABCD, com AD = BC = 4 cm. M é o ponto médio de  e o ângulo BMC é reto.

e o ângulo BMC é reto.

Três números estão em progressão geométrica de razão - FGV 2014

Matemática - 2014Três números estão em progressão geométrica de razão 3/2 Diminuindo 5 unidades do terceiro número da progressão, ela se transforma em uma progressão aritmética.

Dos animais de uma fazenda, 40% são bois, 30% vacas, e os - FGV 2015

Matemática - 2014Dos animais de uma fazenda, 40% são bois, 30% vacas, e os demais são caprinos. Se o dono da fazenda vende 30% dos bois e 70% das vacas,

No período – ... até que alguém perceba que ele é o - FGV 2014

Língua Portuguesa - 2014Leia o texto para responder à questão

Com o tempo, o líder ruim se distancia completamente da equipe. A consequência é que ele acaba perdendo a legitimidade. A partir desse momento, o clima de trabalho vai piorar muito. Os resultados da área vão começar a despencar. Se o líder tiver muito destaque na empresa, talvez leve tempo até que alguém perceba que ele é o responsável. Se a coisa está nesse ponto, ficar no emprego é uma aposta arriscada.

(Você S/A, setembro de 2013. Adaptado)

Uma continuidade ao texto, correta quanto à norma-padrão, : - FGV 2014

Língua Portuguesa - 2014Leia o texto para responder à questão

Com o tempo, o líder ruim se distancia completamente da equipe. A consequência é que ele acaba perdendo a legitimidade. A partir desse momento, o clima de trabalho vai piorar muito. Os resultados da área vão começar a despencar. Se o líder tiver muito destaque na empresa, talvez leve tempo até que alguém perceba que ele é o responsável. Se a coisa está nesse ponto, ficar no emprego é uma aposta arriscada.

(Você S/A, setembro de 2013. Adaptado)

Considere os enunciados. • O acesso ao celular no Brasil é u- FGV 2014

Língua Portuguesa - 2014Considere os enunciados.

• O acesso ao celular no Brasil é uma fotografia idêntica ____ da renda. Quanto menor a remuneração numa região, mais baixa é a penetração do telefone móvel.

• As trajetórias de Caetano Veloso, Chico Buarque e Gilberto Gil sem dúvida merecem consideração. Gosto ____ parte, o valor artístico de suas obras – assim como as de Djavan, Erasmo Carlos e Milton Nascimento – também é patente.

• No mês passado, atracou no porto de Roterdã, na Holanda, o primeiro navio cargueiro chinês ____ navegar até ____ Europa pelo Ártico.

Resolução adaptada de: Curso Objetivo

Assinale a alternativa em que o trecho contém discurso - FGV 2014

Língua Portuguesa - 2014Assinale a alternativa

Entre os muitos empregos que a preposição de pode ter, um - FGV 2014

Língua Portuguesa - 2014Leia o texto para responder à questão

O resgate do cocô

Há três mil anos, quando um chinês ia jantar na casa de um amigo, ele obrigatoriamente tinha que ir até o quintal desse amigo e fazer um “número dois” por lá mesmo. É que a etiqueta da época dizia que era feio comer na casa de alguém e não “devolver os nutrientes”. Faz tanto sentido que, atualmente, o arquiteto William Mc Donough e o químico Michel Braungart trabalham para trazer essa ideia de volta à moda, desenvolvendo e divulgando modos de produção circular, em que os resíduos – inclusive o cocô – são usados para criar novos produtos tão bons quanto os originais.

Baseados na proposta de Mc Donough e Braungart, pesquisadores do mundo inteiro têm procurado maneiras de aproveitar o nosso “número dois” de cada dia. Na cidade de Didcot, na Inglaterra, um projeto piloto já permite que 200 famílias aqueçam suas casas com biometano fabricado a partir de seu próprio cocô. Além de poupar o meio ambiente, eles economizam dinheiro. Uma ideia que cheira bem.

(Superinteressante, agosto de 2013. Adaptado)

Assinale a alternativa correta quanto à pontuação. a) Na - FGV 2014

Língua Portuguesa - 2014Leia o texto para responder à questão

O resgate do cocô

Há três mil anos, quando um chinês ia jantar na casa de um amigo, ele obrigatoriamente tinha que ir até o quintal desse amigo e fazer um “número dois” por lá mesmo. É que a etiqueta da época dizia que era feio comer na casa de alguém e não “devolver os nutrientes”. Faz tanto sentido que, atualmente, o arquiteto William Mc Donough e o químico Michel Braungart trabalham para trazer essa ideia de volta à moda, desenvolvendo e divulgando modos de produção circular, em que os resíduos – inclusive o cocô – são usados para criar novos produtos tão bons quanto os originais.

Baseados na proposta de Mc Donough e Braungart, pesquisadores do mundo inteiro têm procurado maneiras de aproveitar o nosso “número dois” de cada dia. Na cidade de Didcot, na Inglaterra, um projeto piloto já permite que 200 famílias aqueçam suas casas com biometano fabricado a partir de seu próprio cocô. Além de poupar o meio ambiente, eles economizam dinheiro. Uma ideia que cheira bem.

(Superinteressante, agosto de 2013. Adaptado)

Em virtude do contexto sintático de seu emprego, a palavra - FGV 2014

Língua Portuguesa - 2014Leia o texto para responder à questão

O resgate do cocô

Há três mil anos, quando um chinês ia jantar na casa de um amigo, ele obrigatoriamente tinha que ir até o quintal desse amigo e fazer um “número dois” por lá mesmo. É que a etiqueta da época dizia que era feio comer na casa de alguém e não “devolver os nutrientes”. Faz tanto sentido que, atualmente, o arquiteto William Mc Donough e o químico Michel Braungart trabalham para trazer essa ideia de volta à moda, desenvolvendo e divulgando modos de produção circular, em que os resíduos – inclusive o cocô – são usados para criar novos produtos tão bons quanto os originais.

Baseados na proposta de Mc Donough e Braungart, pesquisadores do mundo inteiro têm procurado maneiras de aproveitar o nosso “número dois” de cada dia. Na cidade de Didcot, na Inglaterra, um projeto piloto já permite que 200 famílias aqueçam suas casas com biometano fabricado a partir de seu próprio cocô. Além de poupar o meio ambiente, eles economizam dinheiro. Uma ideia que cheira bem.

(Superinteressante, agosto de 2013. Adaptado)

Assinale a alternativa em que a reescrita altera o sentido - FGV 2014

Língua Portuguesa - 2014Leia o texto para responder à questão

O resgate do cocô

Há três mil anos, quando um chinês ia jantar na casa de um amigo, ele obrigatoriamente tinha que ir até o quintal desse amigo e fazer um “número dois” por lá mesmo. É que a etiqueta da época dizia que era feio comer na casa de alguém e não “devolver os nutrientes”. Faz tanto sentido que, atualmente, o arquiteto William Mc Donough e o químico Michel Braungart trabalham para trazer essa ideia de volta à moda, desenvolvendo e divulgando modos de produção circular, em que os resíduos – inclusive o cocô – são usados para criar novos produtos tão bons quanto os originais.

Baseados na proposta de Mc Donough e Braungart, pesquisadores do mundo inteiro têm procurado maneiras de aproveitar o nosso “número dois” de cada dia. Na cidade de Didcot, na Inglaterra, um projeto piloto já permite que 200 famílias aqueçam suas casas com biometano fabricado a partir de seu próprio cocô. Além de poupar o meio ambiente, eles economizam dinheiro. Uma ideia que cheira bem.

(Superinteressante, agosto de 2013. Adaptado)

No texto, emprega-se a expressão “número dois” com a - FGV 2014

Língua Portuguesa - 2014Leia o texto para responder à questão

O resgate do cocô

Há três mil anos, quando um chinês ia jantar na casa de um amigo, ele obrigatoriamente tinha que ir até o quintal desse amigo e fazer um “número dois” por lá mesmo. É que a etiqueta da época dizia que era feio comer na casa de alguém e não “devolver os nutrientes”. Faz tanto sentido que, atualmente, o arquiteto William Mc Donough e o químico Michel Braungart trabalham para trazer essa ideia de volta à moda, desenvolvendo e divulgando modos de produção circular, em que os resíduos – inclusive o cocô – são usados para criar novos produtos tão bons quanto os originais.

Baseados na proposta de Mc Donough e Braungart, pesquisadores do mundo inteiro têm procurado maneiras de aproveitar o nosso “número dois” de cada dia. Na cidade de Didcot, na Inglaterra, um projeto piloto já permite que 200 famílias aqueçam suas casas com biometano fabricado a partir de seu próprio cocô. Além de poupar o meio ambiente, eles economizam dinheiro. Uma ideia que cheira bem.

(Superinteressante, agosto de 2013. Adaptado)

BERLIM, 7 Out (Reuters) – O Partido Social-Democrata (SPD, - FGV 2014

Língua Portuguesa - 2014BERLIM, 7 Out (Reuters) – O Partido Social-Democrata (SPD, na sigla em alemão), de oposição, __________ estar disposto a se juntar aos conservadores da chanceler alemã, Angela Merkel, ao reduzir a demanda eleitoral por elevação de impostos para os ricos. No entanto, resta saber se membros históricos do SPD vão apoiar uma __________ ampla, devido __________ temor _________ a imagem do mais antigo partido alemão possa se deteriorar ainda mais em um governo liderado pela popular Merkel.

A locução empregada no poema com valor de adjetivo é: a) - FGV 2014

Língua Portuguesa - 2014Leia o poema de Mário Quintana para responder à questão

Um céu comum

No Céu vou ser recebido

com uma banda de música.

Tocarão um dobradinho

daqueles que nós sabemos

– pois nada mais celestial

do que a música que um dia ouvimos

no coreto municipal

de nossa cidadezinha...

Não ________ cítaras nem liras

– quem pensam vocês que eu sou?

E os anjinhos estarão vestidos

no uniforme da banda,

com os sovacos bem suados

e os sapatos apertando.

Depois, irei tratar da vida

como eles tratam da sua...

Assinale a alternativa correta em relação às classes de - FGV 2014

Língua Portuguesa - 2014Leia o poema de Mário Quintana para responder à questão

Um céu comum

No Céu vou ser recebido

com uma banda de música.

Tocarão um dobradinho

daqueles que nós sabemos

– pois nada mais celestial

do que a música que um dia ouvimos

no coreto municipal

de nossa cidadezinha...

Não ________ cítaras nem liras

– quem pensam vocês que eu sou?

E os anjinhos estarão vestidos

no uniforme da banda,

com os sovacos bem suados

e os sapatos apertando.

Depois, irei tratar da vida

como eles tratam da sua...

[Os monossílabos] átonos são aqueles pronunciados tão - FUGV 2014

Língua Portuguesa - 2014Leia o poema de Mário Quintana para responder à questão

Um céu comum

No Céu vou ser recebido

com uma banda de música.

Tocarão um dobradinho

daqueles que nós sabemos

– pois nada mais celestial

do que a música que um dia ouvimos

no coreto municipal

de nossa cidadezinha...

Não ________ cítaras nem liras

– quem pensam vocês que eu sou?

E os anjinhos estarão vestidos

no uniforme da banda,

com os sovacos bem suados

e os sapatos apertando.

Depois, irei tratar da vida

como eles tratam da sua...

[Os monossílabos] átonos são aqueles pronunciados tão fracamente que, na frase, precisam apoiar-se no acento tônico de um vocábulo vizinho, formando, por assim dizer, uma sílaba deste.

De acordo com a norma-padrão da língua portuguesa, a lacuna - FGV 2014

Língua Portuguesa - 2014Leia o poema de Mário Quintana para responder à questão

Um céu comum

No Céu vou ser recebido

com uma banda de música.

Tocarão um dobradinho

daqueles que nós sabemos

– pois nada mais celestial

do que a música que um dia ouvimos

no coreto municipal

de nossa cidadezinha...

Não ________ cítaras nem liras

– quem pensam vocês que eu sou?

E os anjinhos estarão vestidos

no uniforme da banda,

com os sovacos bem suados

e os sapatos apertando.

Depois, irei tratar da vida

como eles tratam da sua...

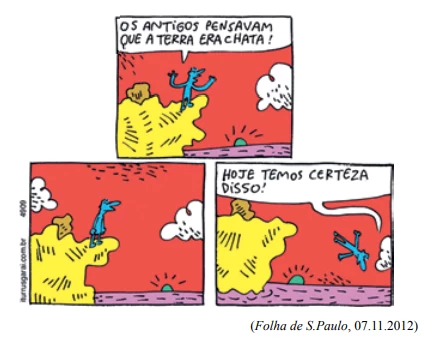

Levando-se em consideração a intenção de humor na tira, os - FGV 2014

Língua Portuguesa - 2014Leia a tira.

De acordo com dados da Agência Internacional de Energia - FGV 2014

Química - 2014De acordo com dados da Agência Internacional de Energia (AIE), aproximadamente 87% de todo o combustível consumido no mundo são de origem fóssil. Essas substâncias são encontradas em diversas regiões do planeta, no estado sólido, líquido e gasoso e são processadas e empregadas de diversas formas.

(www.brasilescola.com/geografia/combustiveis-fosseis.htm. Adaptado)

Por meio de processo de destilação seca, o combustível I dá origem à matéria-prima para a indústria de produção de aço e alumínio.O combustível II é utilizado como combustível veicular, em usos domésticos, na geração de energia elétrica e também como matéria-prima em processos industriais.

O combustível III é obtido por processo de destilação fracionada ou por reação química, e é usado como combustível veicular.

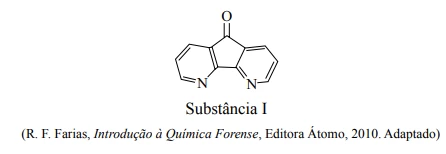

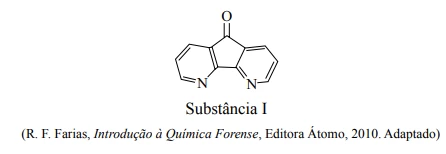

Na estrutura da substância I, observam-se as funções - FGV 2014

Química - 2014texto a seguir refere-se à questão

O conhecimento científico tem sido cada vez mais empregado como uma ferramenta na elucidação de crimes. A química tem fornecido muitas contribuições para a criação da ciência forense. Um exemplo disso são as investigações de impressões digitais empregando-se a substância I (figura). Essa substância interage com resíduos de proteína deixados pelo contato das mãos e, na presença de uma fonte de luz adequada, luminesce e revela vestígios imperceptíveis a olho nu.

A fórmula molecular e o total de ligações sigma na molécula - FGV 2014

Química - 2014texto a seguir refere-se à questão

O conhecimento científico tem sido cada vez mais empregado como uma ferramenta na elucidação de crimes. A química tem fornecido muitas contribuições para a criação da ciência forense. Um exemplo disso são as investigações de impressões digitais empregando-se a substância I (figura). Essa substância interage com resíduos de proteína deixados pelo contato das mãos e, na presença de uma fonte de luz adequada, luminesce e revela vestígios imperceptíveis a olho nu.

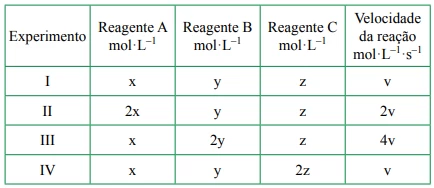

Para otimizar as condições de um processo industrial que - FGV 2014

Química - 2014Para otimizar as condições de um processo industrial que depende de uma reação de soluções aquosas de três diferentes reagentes para a formação de um produto, um engenheiro químico realizou um experimento que consistiu em uma série de reações nas mesmas condições de temperatura e agitação. Os resultados são apresentados na tabela:

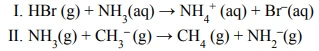

A amônia é um composto muito versátil, pois seu - FGV 2014

Química - 2014A amônia é um composto muito versátil, pois seu comportamento químico possibilita seu emprego em várias reações químicas em diversos mecanismos reacionais, como em

De acordo com o conceito ácido-base de Lewis, em I a amônia é classificada como _________. De acordo com o conceito ácido-base de Brösnted-Lowry, a amônia é classificada em I e II, respectivamente, como_________ e _________.

A indústria alimentícia emprega várias substâncias químicas - FGV 2014

Química - 2014A indústria alimentícia emprega várias substâncias químicas para conservar os alimentos e garantir que eles se mantenham adequados para consumo após a fabricação, transporte e armazenagem nos pontos de venda. Dois exemplos disso são o nitrato de sódio adicionado nos produtos derivados de carnes e o sorbato de potássio, proveniente do ácido sórbico HC6H7O2 (Ka = 2 x 10–5 a 25°C), usado na fabricação de queijos.

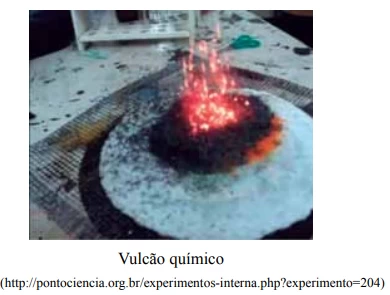

O composto inorgânico alaranjado dicromato de amônio, - FGV 2014

Química - 2014O composto inorgânico alaranjado dicromato de amônio, (NH4)2 Cr2 O7 , quando aquecido sofre decomposição térmica em um processo que libera água na forma de vapor, gás nitrogênio e também forma o óxido de cromo (III). Esse fenômeno ocorre com uma grande expansão de volume e, por isso, é usado em simulações de efeitos de explosões vulcânicas com a denominação de vulcão químico.

O Brasil é um grande produtor e exportador de suco - FGV 2014

Química - 2014O Brasil é um grande produtor e exportador de suco concentrado de laranja. O suco in natura é obtido a partir de processo de prensagem da fruta que, após a separação de cascas e bagaços, possui 12% em massa de sólidos totais, solúveis e insolúveis. A preparação do suco concentrado é feita por evaporação de água até que se atinja o teor de sólidos totais de 48% em massa

Considere os dados da tabela: O valor da entalpia padrão - FGV 2014

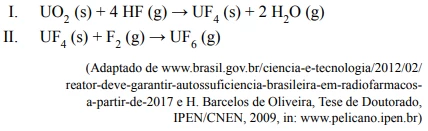

Química - 2014O texto seguinte refere-se à questão

Deverá entrar em funcionamento em 2017, em Iperó, no interior de São Paulo, o Reator Multipropósito Brasileiro (RMB), que será destinado à produção de radioisótopos para radiofármacos e também para produção de fontes radioativas usadas pelo Brasil em larga escala nas áreas industrial e de pesquisas. Um exemplo da aplicação tecnológica de radioisótopos são sensores contendo fonte de amerício-241, obtido como produto de fissão. Ele decai para o radioisótopo neptúnio-237 e emite um feixe de radiação. Fontes de amerício-241 são usadas como indicadores de nível em tanques e fornos mesmo em ambiente de intenso calor, como ocorre no interior dos alto fornos da Companhia Siderúrgica Paulista (COSIPA).

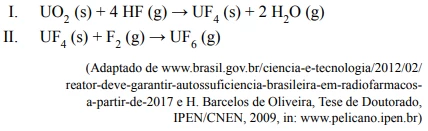

A produção de combustível para os reatores nucleares de fissão envolve o processo de transformação do composto sólido UO2 ao composto gasoso UF6 por meio das etapas:

Considerando o tipo de reator mencionado no texto, - FGV 2014

Química - 2014O texto seguinte refere-se à questão

Deverá entrar em funcionamento em 2017, em Iperó, no interior de São Paulo, o Reator Multipropósito Brasileiro (RMB), que será destinado à produção de radioisótopos para radiofármacos e também para produção de fontes radioativas usadas pelo Brasil em larga escala nas áreas industrial e de pesquisas. Um exemplo da aplicação tecnológica de radioisótopos são sensores contendo fonte de amerício-241, obtido como produto de fissão. Ele decai para o radioisótopo neptúnio-237 e emite um feixe de radiação. Fontes de amerício-241 são usadas como indicadores de nível em tanques e fornos mesmo em ambiente de intenso calor, como ocorre no interior dos alto fornos da Companhia Siderúrgica Paulista (COSIPA).

A produção de combustível para os reatores nucleares de fissão envolve o processo de transformação do composto sólido UO2 ao composto gasoso UF6 por meio das etapas:

No decaimento do amerício-241 a neptúnio-237, há emissão de - FGV 2014

Química - 2014O texto seguinte refere-se à questão

Deverá entrar em funcionamento em 2017, em Iperó, no interior de São Paulo, o Reator Multipropósito Brasileiro (RMB), que será destinado à produção de radioisótopos para radiofármacos e também para produção de fontes radioativas usadas pelo Brasil em larga escala nas áreas industrial e de pesquisas. Um exemplo da aplicação tecnológica de radioisótopos são sensores contendo fonte de amerício-241, obtido como produto de fissão. Ele decai para o radioisótopo neptúnio-237 e emite um feixe de radiação. Fontes de amerício-241 são usadas como indicadores de nível em tanques e fornos mesmo em ambiente de intenso calor, como ocorre no interior dos alto fornos da Companhia Siderúrgica Paulista (COSIPA).

A produção de combustível para os reatores nucleares de fissão envolve o processo de transformação do composto sólido UO2 ao composto gasoso UF6 por meio das etapas:

Créditos de carbono são certificações dadas a empresas, - FGV 2014

Química - 2014Créditos de carbono são certificações dadas a empresas, indústrias e países que conseguem reduzir a emissão de gases poluentes na atmosfera. Cada tonelada de CO2 não emitida ou retirada da atmosfera equivale a um crédito de carbono.

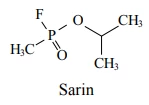

Armas químicas são baseadas na toxicidade de substâncias, - FGV 2014

Química - 2014Armas químicas são baseadas na toxicidade de substâncias, capazes de matar ou causar danos a pessoas e ao meio ambiente. Elas têm sido utilizadas em grandes conflitos e guerras, como o ocorrido em 2013 na Síria, quando a ação do sarin causou a morte de centenas de civis.

(http://pt.wikipedia.org/wiki/Guerra_qu%C3%ADmica e http://pt.wikipedia.org/wiki/Categoria:Armas_qu%C3%ADmicas. Adaptado)

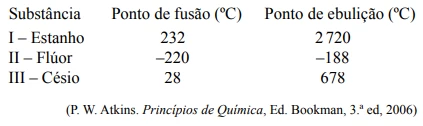

O conhecimento das propriedades físico-químicas das - FGV 2014

Química - 2014O conhecimento das propriedades físico-químicas das substâncias é muito útil para avaliar condições adequadas para a sua armazenagem e transporte.

Considere os dados das três substâncias seguintes:

Uma nova e promissora classe de materiais supercondutores - FGV 2014

Química - 2014Uma nova e promissora classe de materiais supercondutores tem como base o composto diboreto de zircônio e vanádio. Esse composto é sintetizado a partir de um sal de zircônio (IV).

O rendimento do aparelho será mais próximo de a) 82%. b) - FGV 2014

Física - 2014O texto e as informações a seguir referem-se às questão.

Uma pessoa adquiriu um condicionador de ar para instalá-lo em determinado ambiente. O manual de instruções do aparelho traz, dentre outras, as seguintes especificações: 9000 BTUs; voltagem: 220 V; corrente: 4,1 A; potência: 822 W.

Considere que BTU é uma unidade de energia equivalente a 250 calorias e que o aparelho seja utilizado para esfriar o ar de um ambiente de 15 m de comprimento, por 10 m de largura, por 4 m de altura. O calor específico do ar é de 0,25 cal/(g·o C) e a sua densidade é de 1,25 kg/m3 .

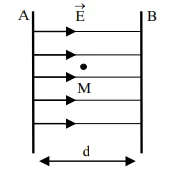

Duas placas metálicas planas A e B, dispostas paralela e - FGV 2014

Física - 2014Duas placas metálicas planas A e B, dispostas paralela e verticalmente a uma distância mútua d, são eletrizadas com cargas iguais, mas de sinais opostos, criando um campo elétrico uniforme  em seu interior, onde se produz um vácuo. A figura mostra algumas linhas de força na região mencionada.

em seu interior, onde se produz um vácuo. A figura mostra algumas linhas de força na região mencionada.

Uma partícula, de massa m e carga positiva q, é abandonada do repouso no ponto médio M entre as placas. Desprezados os efeitos gravitacionais, essa partícula deverá atingir a placa ______ com velocidade v dada por ________.

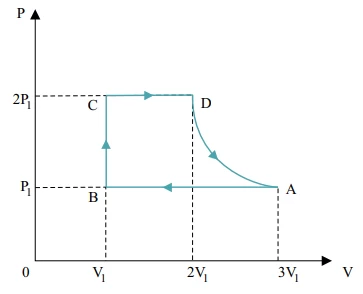

O gráfico da pressão (P), em função do volume (V) de um gás - FGV 2014

Física - 2014O gráfico da pressão (P), em função do volume (V) de um gás perfeito, representa um ciclo de transformações a que o gás foi submetido.

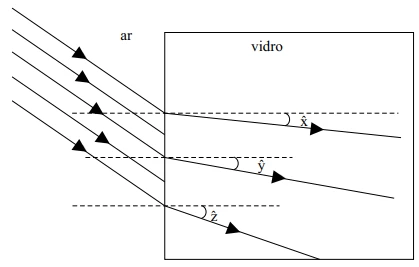

Um feixe de luz branca do Sol, vindo do ar, encontra um - FGV 2014

Física - 2014Um feixe de luz branca do Sol, vindo do ar, encontra um bloco cúbico de vidro sobre o qual incide obliquamente; refrata dispersando-se em forma de leque em seu interior.

A lupa é um instrumento óptico constituído por uma lente de - FGV 2014

Física - 2014A lupa é um instrumento óptico constituído por uma lente de aumento.

A relação RT/RL entre os raios das superfícies da Terra - FGV 2014

Física - 2014A relação RT/RL entre os raios das superfícies da Terra (RT)

Na superfície lunar, uma pequena bola lançada a partir do - FGV 2014

Física - 2014As informações seguintes referem-se à questão

Aceleração da gravidade na superfície da Terra: gT = 10 m/s2 ; aceleração da gravidade na superfície da Lua: gL = 1,6 m/s2 ; massa da Terra igual a 81 vezes a massa da Lua; sen45o = cos45o = √2/2.

Na loja de um supermercado, uma cliente lança seu carrinho - FGV 2014

Física - 2014Na loja de um supermercado, uma cliente lança seu carrinho com compras, de massa total 30 kg, em outro carrinho vazio, parado e de massa 20 kg. Ocorre o engate entre ambos e, como consequência do engate, o conjunto dos carrinhos percorre 6,0 m em 4,0 s, perdendo velocidade de modo uniforme até parar. O sistema de carrinhos é considerado isolado durante o engate.

Um pequeno submarino teleguiado, pesando 1 200N no ar, - FGV 2014

Física - 2014Um pequeno submarino teleguiado, pesando 1 200N no ar, movimenta-se totalmente submerso no mar em movimento horizontal, retilíneo e uniforme a 36km/h. Seu sistema propulsor desenvolve uma potência de 40kW.

O trabalho realizado pela resultante das forças agentes - FGV 2014

Física - 2014O trabalho realizado pela resultante das forças agentes sobre o automóvel foi,

Com a velocidade crescendo de modo constante, em função do - FGV 2014

Física - 2014O texto seguinte refere-se à questão.

Em alguns países da Europa, os radares fotográficos das rodovias, além de detectarem a velocidade instantânea dos veículos, são capazes de determinar a velocidade média desenvolvida pelos veículos entre dois radares consecutivos.

Considere dois desses radares instalados em uma rodovia retilínea e horizontal. A velocidade instantânea de certo automóvel, de 1 500 kg de massa, registrada pelo primeiro radar foi de 72 km/h. Um minuto depois, o radar seguinte acusou 90 km/h para o mesmo automóvel.

Na função horária S = B·t2 + A, em que S representa as - FGV 2014

Física - 2014Na função horária S = B·t2 + A, em que S representa as posições ocupadas por um móvel sobre uma trajetória retilínea em função do tempo t,

A medida de certo comprimento foi apresentada com o valor - FGV 2014

Física - 2014A medida de certo comprimento foi apresentada com o valor 2,954·103 m. Levando-se em conta a teoria dos algarismos significativos,

The sentence from the tenth paragraph – Rather than - FGV 2014

Inglês - 2014Read the article and answer the question

The road to hell

(1) Bringing crops from one of the futuristic new farms in Brazil’s central and northern plains to foreign markets means taking a journey back in time. Loaded onto lorries, most are driven almost 2,000km south on narrow, potholed roads to the ports of Santos and Paranaguá. In the 19th and early 20th centuries they were used to bring in immigrants and ship out the coffee grown in the fertile states of São Paulo and Paraná, but now they are overwhelmed. Thanks to a record harvest this year, Brazil became the world’s largest soya producer, overtaking the United States. The queue of lorries waiting to enter Santos sometimes stretched to 40km.

(2) No part of that journey makes sense. Brazil has too few crop silos, so lorries are used for storage as well as transport, causing a crush at ports after harvest. Produce from so far north should probably not be travelling to southern ports at all. Freight by road costs twice as much as by rail and four times as much as by water. Brazilian farmers pay 25% or more of the value of their soya to bring it to port; their competitors in Iowa just 9%. The bottleneck at ports pushes costs higher still. It also puts off customers. In March Sunrise Group, China’s biggest soya trader, cancelled an order for 2m tonnes of Brazilian soya after repeated delays.

(3) All of Brazil’s infrastructure is decrepit. The World Economic Forum ranks it at 114th out of 148 countries. After a spate of railway-building at the turn of the 20th century, and road- and dam-building 50 years later, little was added or even maintained. In the 1980s infrastructure was a casualty of slowing growth and spiralling inflation. Unable to find jobs, engineers emigrated or retrained. Government stopped planning for the long term. According to Contas Abertas, a public-spending watchdog, only a fifth of federal money budgeted for urban transport in the past decade was actually spent. Just 1.5% of Brazil’s GDP goes on infrastructure investment from all sources, both public and private. The long-run global average is 3.8%. The McKinsey Global Institute estimates the total value of Brazil’s infrastructure at 16% of GDP. Other big economies average 71%. To catch up, Brazil would have to triple its annual infrastructure spending for the next 20 years.

(4) Moreover, it may be getting poor value from what little it does invest because so much goes on the wrong things. A cumbersome environmental-licensing process pushes up costs and causes delays. Expensive studies are required before construction on big projects can start and then again at various stages along the way and at the end. Farmers and manufacturers spend heavily on lorries because road transport is their only option. But that is working around the problem, not solving it.

(5) In the 1990s Mr Cardoso’s government privatised state-owned oil, energy and telecoms firms. It allowed private operators to lease terminals in public ports and to build their own new ports. Imports were booming as the economy opened up, so container terminals were a priority. The one at the public port in Bahia’s capital, Salvador, is an example of the transformation wrought by private money and management. Its customers used to rate it Brazil’s worst port, with a draft too shallow for big ships and a quay so short that even smaller vessels had to unload a bit at a time. But in the past decade its operator, Wilson & Sons, spent 260m reais on replacing equipment, lengthening the quay and deepening the draft. Capacity has doubled. Land access will improve, too, once an almost finished expressway opens. Paranaguá is spending 400m reais from its own revenues on replacing outdated equipment, but without private money it cannot expand enough to end the queues to dock. It has drawn up detailed plans to build a new terminal and two new quays, and identified 20 dockside areas that could be leased to new operators, which would bring in 1.6 billion reais of private investment. All that is missing is the federal government’s permission. It hopes to get it next year, but there is no guarantee.

(6) Firms that want to build their own infrastructure, such as mining companies, which need dedicated railways and ports, can generally build at will in Brazil, though they still face the hassle of environmental licensing. If the government wants to hand a project to the private sector it will hold an auction, granting the concession to the highest bidder, or sometimes the applicant who promises the lowest user charges. But since Lula came to power in 2003 there have been few infrastructure auctions of any kind. In recent years, under heavy lobbying from public ports, the ports regulator stopped granting operating licences to private ports except those intended mainly for the owners’ own cargo. As a result, during a decade in which Brazil became a commodity-exporting powerhouse, its bulk-cargo terminals hardly expanded at all.

(7) At first Lula’s government planned to upgrade Brazil’s infrastructure without private help. In 2007 the president announced a collection of long-mooted public construction projects, the Growth Acceleration Programme (PAC). Many were intended to give farming and mining regions access to alternative ports. But the results have been disappointing. Two-thirds of the biggest projects are late and over budget. The trans-north-eastern railway is only half-built and its cost has doubled. The route of the east-west integration railway, which would cross Bahia, has still not been settled. The northern stretch of the BR-163, a trunk road built in the 1970s, was waiting so long to be paved that locals started calling it the “endless road”. Most of it is still waiting.

(8) What has got things moving is the prospect of disgrace during the forthcoming big sporting events. Brazil’s terrible airports will be the first thing most foreign football fans see when they arrive for next year’s World Cup. Infraero, the state-owned company that runs them, was meant to be getting them ready for the extra traffic, but it is a byword for incompetence. Between 2007 and 2010 it managed to spend just 800m of the 3 billion reais it was supposed to invest. In desperation, the government last year leased three of the biggest airports to private operators.

(9) That seemed to break a bigger logjam. First more airport auctions were mooted; then, some months later, Ms Rousseff announced that 7,500km of toll roads and 10,000km of railways were to be auctioned too. Earlier this year she picked the biggest fight of her presidency, pushing a ports bill through Congress against lobbying from powerful vested interests. The new law enables private ports once again to handle third-party cargo and allows them to hire their own staff, rather than having to use casual labour from the dockworkers’ unions that have a monopoly in public ports. Ms Rousseff also promised to auction some entirely new projects and to re-tender around 150 contracts in public terminals whose concessions had expired.

(10) Would-be investors in port projects are hanging back because of the high chances of cost overruns and long delays. Two newly built private terminals at Santos that together cost more than 4 billion reais illustrate the risks. Both took years to get off the ground and years more to build. Both were finished earlier this year but remained idle for months. Brasil Terminal Portuário, a private terminal within the public port, is still waiting for the government to dredge its access channel. At Embraport, which is outside the public-port area, union members from Santos blocked road access and boarded any ships that tried to dock. Rather than enforcing the law that allows such terminals to use their own workers, the government summoned the management to Brasília for some arm-twisting. In August Embraport agreed to take the union members “on a trial basis”.

(11) Given such regulatory and execution risks, there are unlikely to be many takers for either rail or port projects as currently conceived, says Bruno Savaris, an infrastructure analyst at Credit Suisse. He predicts that at most a third of the planned investments will be auctioned in the next three years: airports, a few simple port projects and the best toll roads. That is far short of what Brazil needs. The good news, says Mr Savaris, is that the government is at last beginning to understand that it must either reduce the risks for private investors or raise their returns. Private know-how and money will be vital to get Brazil moving again.

(www.economist.com/news/special-report. Adapted)

As regards infrastructure auctioning as mentioned in the - FGV 2014

Inglês - 2014Read the article and answer the question

The road to hell

(1) Bringing crops from one of the futuristic new farms in Brazil’s central and northern plains to foreign markets means taking a journey back in time. Loaded onto lorries, most are driven almost 2,000km south on narrow, potholed roads to the ports of Santos and Paranaguá. In the 19th and early 20th centuries they were used to bring in immigrants and ship out the coffee grown in the fertile states of São Paulo and Paraná, but now they are overwhelmed. Thanks to a record harvest this year, Brazil became the world’s largest soya producer, overtaking the United States. The queue of lorries waiting to enter Santos sometimes stretched to 40km.

(2) No part of that journey makes sense. Brazil has too few crop silos, so lorries are used for storage as well as transport, causing a crush at ports after harvest. Produce from so far north should probably not be travelling to southern ports at all. Freight by road costs twice as much as by rail and four times as much as by water. Brazilian farmers pay 25% or more of the value of their soya to bring it to port; their competitors in Iowa just 9%. The bottleneck at ports pushes costs higher still. It also puts off customers. In March Sunrise Group, China’s biggest soya trader, cancelled an order for 2m tonnes of Brazilian soya after repeated delays.

(3) All of Brazil’s infrastructure is decrepit. The World Economic Forum ranks it at 114th out of 148 countries. After a spate of railway-building at the turn of the 20th century, and road- and dam-building 50 years later, little was added or even maintained. In the 1980s infrastructure was a casualty of slowing growth and spiralling inflation. Unable to find jobs, engineers emigrated or retrained. Government stopped planning for the long term. According to Contas Abertas, a public-spending watchdog, only a fifth of federal money budgeted for urban transport in the past decade was actually spent. Just 1.5% of Brazil’s GDP goes on infrastructure investment from all sources, both public and private. The long-run global average is 3.8%. The McKinsey Global Institute estimates the total value of Brazil’s infrastructure at 16% of GDP. Other big economies average 71%. To catch up, Brazil would have to triple its annual infrastructure spending for the next 20 years.

(4) Moreover, it may be getting poor value from what little it does invest because so much goes on the wrong things. A cumbersome environmental-licensing process pushes up costs and causes delays. Expensive studies are required before construction on big projects can start and then again at various stages along the way and at the end. Farmers and manufacturers spend heavily on lorries because road transport is their only option. But that is working around the problem, not solving it.

(5) In the 1990s Mr Cardoso’s government privatised state-owned oil, energy and telecoms firms. It allowed private operators to lease terminals in public ports and to build their own new ports. Imports were booming as the economy opened up, so container terminals were a priority. The one at the public port in Bahia’s capital, Salvador, is an example of the transformation wrought by private money and management. Its customers used to rate it Brazil’s worst port, with a draft too shallow for big ships and a quay so short that even smaller vessels had to unload a bit at a time. But in the past decade its operator, Wilson & Sons, spent 260m reais on replacing equipment, lengthening the quay and deepening the draft. Capacity has doubled. Land access will improve, too, once an almost finished expressway opens. Paranaguá is spending 400m reais from its own revenues on replacing outdated equipment, but without private money it cannot expand enough to end the queues to dock. It has drawn up detailed plans to build a new terminal and two new quays, and identified 20 dockside areas that could be leased to new operators, which would bring in 1.6 billion reais of private investment. All that is missing is the federal government’s permission. It hopes to get it next year, but there is no guarantee.

(6) Firms that want to build their own infrastructure, such as mining companies, which need dedicated railways and ports, can generally build at will in Brazil, though they still face the hassle of environmental licensing. If the government wants to hand a project to the private sector it will hold an auction, granting the concession to the highest bidder, or sometimes the applicant who promises the lowest user charges. But since Lula came to power in 2003 there have been few infrastructure auctions of any kind. In recent years, under heavy lobbying from public ports, the ports regulator stopped granting operating licences to private ports except those intended mainly for the owners’ own cargo. As a result, during a decade in which Brazil became a commodity-exporting powerhouse, its bulk-cargo terminals hardly expanded at all.

(7) At first Lula’s government planned to upgrade Brazil’s infrastructure without private help. In 2007 the president announced a collection of long-mooted public construction projects, the Growth Acceleration Programme (PAC). Many were intended to give farming and mining regions access to alternative ports. But the results have been disappointing. Two-thirds of the biggest projects are late and over budget. The trans-north-eastern railway is only half-built and its cost has doubled. The route of the east-west integration railway, which would cross Bahia, has still not been settled. The northern stretch of the BR-163, a trunk road built in the 1970s, was waiting so long to be paved that locals started calling it the “endless road”. Most of it is still waiting.

(8) What has got things moving is the prospect of disgrace during the forthcoming big sporting events. Brazil’s terrible airports will be the first thing most foreign football fans see when they arrive for next year’s World Cup. Infraero, the state-owned company that runs them, was meant to be getting them ready for the extra traffic, but it is a byword for incompetence. Between 2007 and 2010 it managed to spend just 800m of the 3 billion reais it was supposed to invest. In desperation, the government last year leased three of the biggest airports to private operators.

(9) That seemed to break a bigger logjam. First more airport auctions were mooted; then, some months later, Ms Rousseff announced that 7,500km of toll roads and 10,000km of railways were to be auctioned too. Earlier this year she picked the biggest fight of her presidency, pushing a ports bill through Congress against lobbying from powerful vested interests. The new law enables private ports once again to handle third-party cargo and allows them to hire their own staff, rather than having to use casual labour from the dockworkers’ unions that have a monopoly in public ports. Ms Rousseff also promised to auction some entirely new projects and to re-tender around 150 contracts in public terminals whose concessions had expired.

(10) Would-be investors in port projects are hanging back because of the high chances of cost overruns and long delays. Two newly built private terminals at Santos that together cost more than 4 billion reais illustrate the risks. Both took years to get off the ground and years more to build. Both were finished earlier this year but remained idle for months. Brasil Terminal Portuário, a private terminal within the public port, is still waiting for the government to dredge its access channel. At Embraport, which is outside the public-port area, union members from Santos blocked road access and boarded any ships that tried to dock. Rather than enforcing the law that allows such terminals to use their own workers, the government summoned the management to Brasília for some arm-twisting. In August Embraport agreed to take the union members “on a trial basis”.

(11) Given such regulatory and execution risks, there are unlikely to be many takers for either rail or port projects as currently conceived, says Bruno Savaris, an infrastructure analyst at Credit Suisse. He predicts that at most a third of the planned investments will be auctioned in the next three years: airports, a few simple port projects and the best toll roads. That is far short of what Brazil needs. The good news, says Mr Savaris, is that the government is at last beginning to understand that it must either reduce the risks for private investors or raise their returns. Private know-how and money will be vital to get Brazil moving again.

(www.economist.com/news/special-report. Adapted)

As regards Brazilian airports, the text states in the - FGV 2014

Inglês - 2014Read the article and answer the question