2020

Exibindo questões de 1 a 100.

Constituem termos que reforçam o tom pessimista do - UNIFESP 2017

Língua Portuguesa - 2020Para responder a questão, leia o poema “Dissolução”, de Carlos Drummond de Andrade (1902- 1987), que integra o livro Claro enigma, publicado originalmente em 1951.

Escurece, e não me seduz

tatear sequer uma lâmpada.

Pois que aprouve1 ao dia findar,

aceito a noite.

E com ela aceito que brote

uma ordem outra de seres

e coisas não figuradas.

Braços cruzados.

Vazio de quanto amávamos,

mais vasto é o céu. Povoações

surgem do vácuo.

Habito alguma?

E nem destaco minha pele

da confluente escuridão.

Um fim unânime concentra-se

e pousa no ar. Hesitando.

E aquele agressivo espírito

que o dia carreia2 consigo,

já não oprime. Assim a paz,

destroçada.

Vai durar mil anos, ou

extinguir-se na cor do galo?

Esta rosa é definitiva,

ainda que pobre.

Imaginação, falsa demente,

já te desprezo. E tu, palavra.

No mundo, perene trânsito,

calamo-nos.

E sem alma, corpo, és suave.

(Claro enigma, 2012.)

1 aprazer: causar ou sentir prazer; contentar (-se).

2 carrear: carregar.

No trecho do segundo parágrafo “a ‘social comparison’ - UNIFESP 2020

Inglês - 2020Leia o texto para responder a questão.

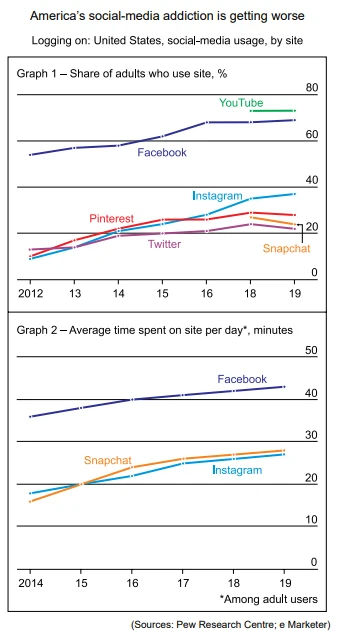

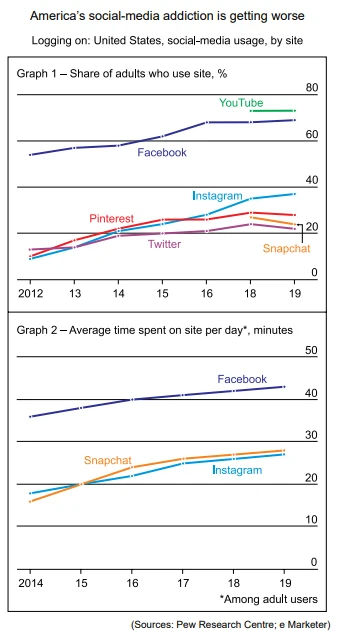

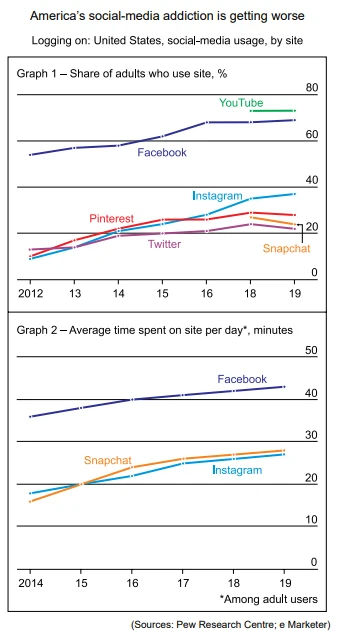

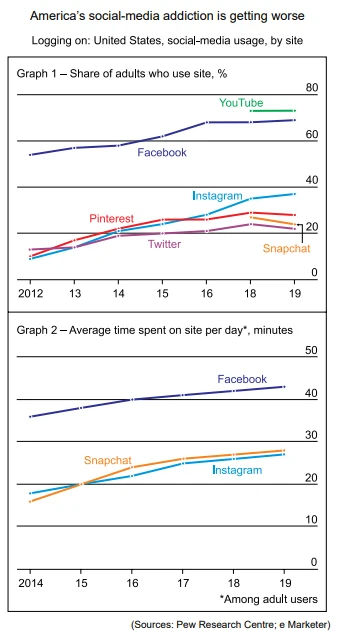

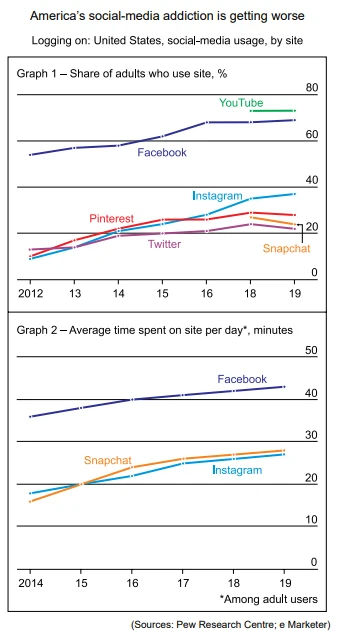

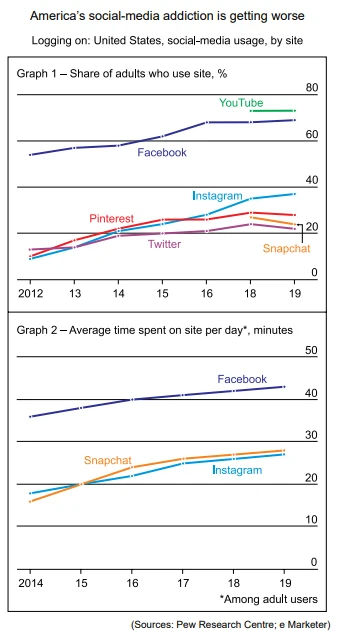

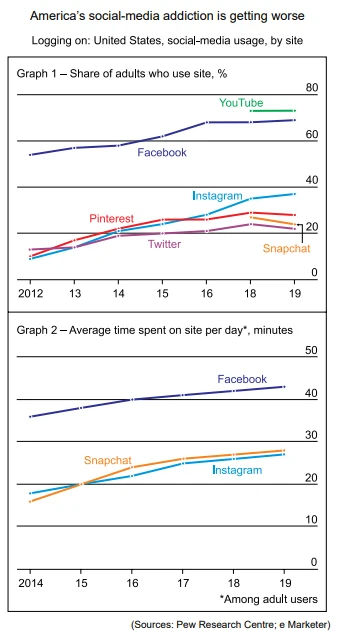

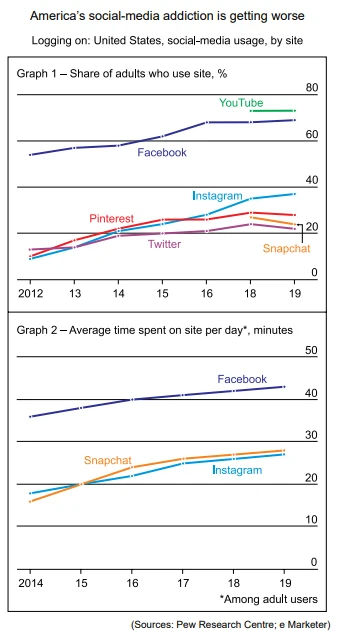

A survey in January and February 2019 from the Pew Research Centre, a think tank, found that 69% of American adults use Facebook; of these users, more than half visit the site “several times a day”. YouTube is even more popular, with 73% of adults saying they watch videos on the platform. For those aged 18 to 24, the figure is 90%. Instagram, a photo-sharing app, is used by 37% of adults. When Pew first conducted the survey in 2012, only a slim majority of Americans used Facebook. Fewer than one in ten had an Instagram account.

Americans are also spending more time than ever on social-media sites like Facebook. There is evidence that limiting such services might yield health benefits. A paper published last year by Melissa Hunt, Rachel Marx, Courtney Lipson and Jordyn Young, all of the University of Pennsylvania, found that limiting social-media usage to 10 minutes a day led to reductions in loneliness, depression, anxiety and fear. Another paper from 2014 identified a link between heavy social-media usage and depression, largely due to a “social comparison” phenomenon, whereby users compare themselves to others and come away with lower evaluations of themselves.

(www.economist.com, 08.08.2019. Adaptado.)

No trecho do segundo parágrafo “largely due to a - UNIFESP 2020

Inglês - 2020Leia o texto para responder a questão.

A survey in January and February 2019 from the Pew Research Centre, a think tank, found that 69% of American adults use Facebook; of these users, more than half visit the site “several times a day”. YouTube is even more popular, with 73% of adults saying they watch videos on the platform. For those aged 18 to 24, the figure is 90%. Instagram, a photo-sharing app, is used by 37% of adults. When Pew first conducted the survey in 2012, only a slim majority of Americans used Facebook. Fewer than one in ten had an Instagram account.

Americans are also spending more time than ever on social-media sites like Facebook. There is evidence that limiting such services might yield health benefits. A paper published last year by Melissa Hunt, Rachel Marx, Courtney Lipson and Jordyn Young, all of the University of Pennsylvania, found that limiting social-media usage to 10 minutes a day led to reductions in loneliness, depression, anxiety and fear. Another paper from 2014 identified a link between heavy social-media usage and depression, largely due to a “social comparison” phenomenon, whereby users compare themselves to others and come away with lower evaluations of themselves.

(www.economist.com, 08.08.2019. Adaptado.)

In the excerpt from the second paragraph “limiting - UNIFESP 2020

Inglês - 2020Leia o texto para responder a questão.

A survey in January and February 2019 from the Pew Research Centre, a think tank, found that 69% of American adults use Facebook; of these users, more than half visit the site “several times a day”. YouTube is even more popular, with 73% of adults saying they watch videos on the platform. For those aged 18 to 24, the figure is 90%. Instagram, a photo-sharing app, is used by 37% of adults. When Pew first conducted the survey in 2012, only a slim majority of Americans used Facebook. Fewer than one in ten had an Instagram account.

Americans are also spending more time than ever on social-media sites like Facebook. There is evidence that limiting such services might yield health benefits. A paper published last year by Melissa Hunt, Rachel Marx, Courtney Lipson and Jordyn Young, all of the University of Pennsylvania, found that limiting social-media usage to 10 minutes a day led to reductions in loneliness, depression, anxiety and fear. Another paper from 2014 identified a link between heavy social-media usage and depression, largely due to a “social comparison” phenomenon, whereby users compare themselves to others and come away with lower evaluations of themselves.

(www.economist.com, 08.08.2019. Adaptado.)

According to the second paragraph, the paper published - UNIFESP 2020

Inglês - 2020Leia o texto para responder a questão.

A survey in January and February 2019 from the Pew Research Centre, a think tank, found that 69% of American adults use Facebook; of these users, more than half visit the site “several times a day”. YouTube is even more popular, with 73% of adults saying they watch videos on the platform. For those aged 18 to 24, the figure is 90%. Instagram, a photo-sharing app, is used by 37% of adults. When Pew first conducted the survey in 2012, only a slim majority of Americans used Facebook. Fewer than one in ten had an Instagram account.

Americans are also spending more time than ever on social-media sites like Facebook. There is evidence that limiting such services might yield health benefits. A paper published last year by Melissa Hunt, Rachel Marx, Courtney Lipson and Jordyn Young, all of the University of Pennsylvania, found that limiting social-media usage to 10 minutes a day led to reductions in loneliness, depression, anxiety and fear. Another paper from 2014 identified a link between heavy social-media usage and depression, largely due to a “social comparison” phenomenon, whereby users compare themselves to others and come away with lower evaluations of themselves.

(www.economist.com, 08.08.2019. Adaptado.)

According to the second paragraph, the excessive use - UNIFESP 2020

Inglês - 2020Leia o texto para responder a questão.

A survey in January and February 2019 from the Pew Research Centre, a think tank, found that 69% of American adults use Facebook; of these users, more than half visit the site “several times a day”. YouTube is even more popular, with 73% of adults saying they watch videos on the platform. For those aged 18 to 24, the figure is 90%. Instagram, a photo-sharing app, is used by 37% of adults. When Pew first conducted the survey in 2012, only a slim majority of Americans used Facebook. Fewer than one in ten had an Instagram account.

Americans are also spending more time than ever on social-media sites like Facebook. There is evidence that limiting such services might yield health benefits. A paper published last year by Melissa Hunt, Rachel Marx, Courtney Lipson and Jordyn Young, all of the University of Pennsylvania, found that limiting social-media usage to 10 minutes a day led to reductions in loneliness, depression, anxiety and fear. Another paper from 2014 identified a link between heavy social-media usage and depression, largely due to a “social comparison” phenomenon, whereby users compare themselves to others and come away with lower evaluations of themselves.

(www.economist.com, 08.08.2019. Adaptado.)

O trecho do primeiro parágrafo “Fewer than one in ten - UNIFESP 2020

Inglês - 2020Leia o texto para responder a questão.

A survey in January and February 2019 from the Pew Research Centre, a think tank, found that 69% of American adults use Facebook; of these users, more than half visit the site “several times a day”. YouTube is even more popular, with 73% of adults saying they watch videos on the platform. For those aged 18 to 24, the figure is 90%. Instagram, a photo-sharing app, is used by 37% of adults. When Pew first conducted the survey in 2012, only a slim majority of Americans used Facebook. Fewer than one in ten had an Instagram account.

Americans are also spending more time than ever on social-media sites like Facebook. There is evidence that limiting such services might yield health benefits. A paper published last year by Melissa Hunt, Rachel Marx, Courtney Lipson and Jordyn Young, all of the University of Pennsylvania, found that limiting social-media usage to 10 minutes a day led to reductions in loneliness, depression, anxiety and fear. Another paper from 2014 identified a link between heavy social-media usage and depression, largely due to a “social comparison” phenomenon, whereby users compare themselves to others and come away with lower evaluations of themselves.

(www.economist.com, 08.08.2019. Adaptado.)

19 No trecho do primeiro parágrafo “of these users, - UNIFESP 2020

Inglês - 2020Leia o texto para responder a questão.

A survey in January and February 2019 from the Pew Research Centre, a think tank, found that 69% of American adults use Facebook; of these users, more than half visit the site “several times a day”. YouTube is even more popular, with 73% of adults saying they watch videos on the platform. For those aged 18 to 24, the figure is 90%. Instagram, a photo-sharing app, is used by 37% of adults. When Pew first conducted the survey in 2012, only a slim majority of Americans used Facebook. Fewer than one in ten had an Instagram account.

Americans are also spending more time than ever on social-media sites like Facebook. There is evidence that limiting such services might yield health benefits. A paper published last year by Melissa Hunt, Rachel Marx, Courtney Lipson and Jordyn Young, all of the University of Pennsylvania, found that limiting social-media usage to 10 minutes a day led to reductions in loneliness, depression, anxiety and fear. Another paper from 2014 identified a link between heavy social-media usage and depression, largely due to a “social comparison” phenomenon, whereby users compare themselves to others and come away with lower evaluations of themselves.

(www.economist.com, 08.08.2019. Adaptado.)

According to the first paragraph and the graphic images - UNIFESP 2020

Inglês - 2020Leia o texto para responder a questão.

A survey in January and February 2019 from the Pew Research Centre, a think tank, found that 69% of American adults use Facebook; of these users, more than half visit the site “several times a day”. YouTube is even more popular, with 73% of adults saying they watch videos on the platform. For those aged 18 to 24, the figure is 90%. Instagram, a photo-sharing app, is used by 37% of adults. When Pew first conducted the survey in 2012, only a slim majority of Americans used Facebook. Fewer than one in ten had an Instagram account.

Americans are also spending more time than ever on social-media sites like Facebook. There is evidence that limiting such services might yield health benefits. A paper published last year by Melissa Hunt, Rachel Marx, Courtney Lipson and Jordyn Young, all of the University of Pennsylvania, found that limiting social-media usage to 10 minutes a day led to reductions in loneliness, depression, anxiety and fear. Another paper from 2014 identified a link between heavy social-media usage and depression, largely due to a “social comparison” phenomenon, whereby users compare themselves to others and come away with lower evaluations of themselves.

(www.economist.com, 08.08.2019. Adaptado.)

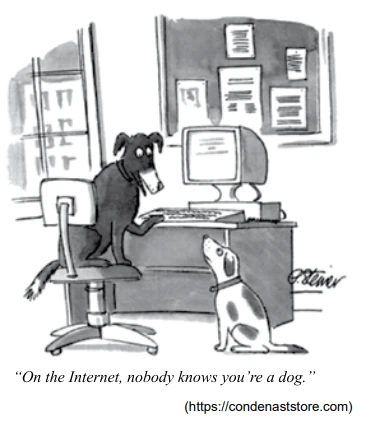

It can be inferred from the phrase “On the Internet, - UNIFESP 2020

Inglês - 2020Examine o quadrinho de Peter Steiner para responder a questão.

The cartoon means that a) both dogs are trying to - UNIFESP 2020

Inglês - 2020Examine o quadrinho de Peter Steiner para responder a questão.

“Deus me livre das bobagens de Lamarck como ‘tendência - UNIFESP 2020

Língua Portuguesa - 2020Para responder a questão, leia o trecho de uma carta de Charles Darwin ao biólogo Joseph Hooker em 11.01.1844.

Além de um interesse geral pelas terras meridionais, desde que retornei tenho me dedicado a um trabalho muito ambicioso que nenhum indivíduo que conheço deixaria de considerar muito bobo. Fiquei tão impressionado com a distribuição dos organismos nas Galápagos e com a natureza dos fósseis de mamíferos americanos, que resolvi recolher todo tipo de coisa que pudesse ter alguma relação com alguma espécie. Li montanhas de livros sobre agricultura e horticultura e não paro de coletar informações. Por fim surgiu uma luz, e estou quase convencido (ao contrário do que achava inicialmente) de que as espécies (é como confessar um homicídio) não são imutáveis. Deus me livre das bobagens de Lamarck como “tendência ao progresso”, “adaptações a partir do esforço dos animais”, — porém minhas conclusões não diferem muito das dele — embora a forma da mudança difira inteiramente — creio que descobri (que presunção!) a maneira simples pela qual as espécies se adaptam a várias finalidades.

(Shaun Usher (org.). Cartas extraordinárias, 2014.)

Em termos figurados, a dimensão transgressora de sua - UNIFESP 2020

Língua Portuguesa - 2020Para responder a questão, leia o trecho de uma carta de Charles Darwin ao biólogo Joseph Hooker em 11.01.1844.

Além de um interesse geral pelas terras meridionais, desde que retornei tenho me dedicado a um trabalho muito ambicioso que nenhum indivíduo que conheço deixaria de considerar muito bobo. Fiquei tão impressionado com a distribuição dos organismos nas Galápagos e com a natureza dos fósseis de mamíferos americanos, que resolvi recolher todo tipo de coisa que pudesse ter alguma relação com alguma espécie. Li montanhas de livros sobre agricultura e horticultura e não paro de coletar informações. Por fim surgiu uma luz, e estou quase convencido (ao contrário do que achava inicialmente) de que as espécies (é como confessar um homicídio) não são imutáveis. Deus me livre das bobagens de Lamarck como “tendência ao progresso”, “adaptações a partir do esforço dos animais”, — porém minhas conclusões não diferem muito das dele — embora a forma da mudança difira inteiramente — creio que descobri (que presunção!) a maneira simples pela qual as espécies se adaptam a várias finalidades.

(Shaun Usher (org.). Cartas extraordinárias, 2014.)

Leia o trecho do poema “Os sapos”, de Manuel Bandeira. - UNIFESP 2020

Língua Portuguesa - 2020Leia o trecho do poema “Os sapos”, de Manuel Bandeira.

O sapo-tanoeiro

[...]

Diz: — “Meu cancioneiro

É bem martelado.

Vede como primo

Em comer os hiatos!

Que arte! E nunca rimo

Os termos cognatos.

O meu verso é bom

Frumento sem joio.

Faço rimas com

Consoantes de apoio.

Vai por cinquenta anos

Que lhes dei a norma:

Reduzi sem danos

A formas a forma.

Clame a saparia

Em críticas céticas:

Não há mais poesia

Mas há artes poéticas...”

Tendo em vista a ordem inversa da frase, verifica-se o - UNIFESP 2020

Língua Portuguesa - 2020Leia a crônica “Inconfiáveis cupins”, de Moacyr Scliar, para responder a questão.

Havia um homem que odiava Van Gogh. Pintor desconhecido, pobre, atribuía todas suas frustrações ao artista holandês. Enquanto existirem no mundo aqueles horríveis girassóis, aquelas estrelas tumultuadas, aqueles ciprestes deformados, dizia, não poderei jamais dar vazão ao meu instinto criador.

Decidiu mover uma guerra implacável, sem quartel, às telas de Van Gogh, onde quer que estivessem. Começaria pelas mais próximas, as do Museu de Arte Moderna de São Paulo.

Seu plano era de uma simplicidade diabólica. Não faria como outros destruidores de telas que entram num museu armados de facas e atiram-se às obras, tentando destruí-las; tais insanos não apenas não conseguem seu intento, como acabam na cadeia. Não, usaria um método científico, recorrendo a aliados absolutamente insuspeitados: os cupins.

Deu-lhe muito trabalho, aquilo. Em primeiro lugar, era necessário treinar os cupins para que atacassem as telas de Van Gogh. Para isso, recorreu a uma técnica pavloviana. Reproduções das telas do artista, em tamanho natural, eram recobertas com uma solução açucarada. Dessa forma, os insetos aprenderam a diferenciar tais obras de outras.

Mediante cruzamentos sucessivos, obteve um tipo de cupim que só queria comer Van Gogh. Para ele era repulsivo, mas para os insetos era agradável, e isso era o que importava. Conseguiu introduzir os cupins no museu e ficou à espera do que aconteceria. Sua decepção, contudo, foi enorme. Em vez de atacar as obras de arte, os cupins preferiram as vigas de sustentação do prédio, feitas de madeira absolutamente vulgar. E por isso foram detectados.

O homem ficou furioso. Nem nos cupins se pode confiar, foi a sua desconsolada conclusão. É verdade que alguns insetos foram encontrados próximos a telas de Van Gogh. Mas isso não lhe serviu de consolo. Suspeitava que os sádicos cupins estivessem querendo apenas debochar dele. Cupins e Van Gogh, era tudo a mesma coisa.

(O imaginário cotidiano, 2002.)

Expressam ideia de negação e ideia de repetição, - UNIFESP 2020

Língua Portuguesa - 2020Leia a crônica “Inconfiáveis cupins”, de Moacyr Scliar, para responder a questão.

Havia um homem que odiava Van Gogh. Pintor desconhecido, pobre, atribuía todas suas frustrações ao artista holandês. Enquanto existirem no mundo aqueles horríveis girassóis, aquelas estrelas tumultuadas, aqueles ciprestes deformados, dizia, não poderei jamais dar vazão ao meu instinto criador.

Decidiu mover uma guerra implacável, sem quartel, às telas de Van Gogh, onde quer que estivessem. Começaria pelas mais próximas, as do Museu de Arte Moderna de São Paulo.

Seu plano era de uma simplicidade diabólica. Não faria como outros destruidores de telas que entram num museu armados de facas e atiram-se às obras, tentando destruí-las; tais insanos não apenas não conseguem seu intento, como acabam na cadeia. Não, usaria um método científico, recorrendo a aliados absolutamente insuspeitados: os cupins.

Deu-lhe muito trabalho, aquilo. Em primeiro lugar, era necessário treinar os cupins para que atacassem as telas de Van Gogh. Para isso, recorreu a uma técnica pavloviana. Reproduções das telas do artista, em tamanho natural, eram recobertas com uma solução açucarada. Dessa forma, os insetos aprenderam a diferenciar tais obras de outras.

Mediante cruzamentos sucessivos, obteve um tipo de cupim que só queria comer Van Gogh. Para ele era repulsivo, mas para os insetos era agradável, e isso era o que importava. Conseguiu introduzir os cupins no museu e ficou à espera do que aconteceria. Sua decepção, contudo, foi enorme. Em vez de atacar as obras de arte, os cupins preferiram as vigas de sustentação do prédio, feitas de madeira absolutamente vulgar. E por isso foram detectados.

O homem ficou furioso. Nem nos cupins se pode confiar, foi a sua desconsolada conclusão. É verdade que alguns insetos foram encontrados próximos a telas de Van Gogh. Mas isso não lhe serviu de consolo. Suspeitava que os sádicos cupins estivessem querendo apenas debochar dele. Cupins e Van Gogh, era tudo a mesma coisa.

(O imaginário cotidiano, 2002.)

Observa-se a elipse de um substantivo no trecho: - UNIFESP 2020

Língua Portuguesa - 2020Leia a crônica “Inconfiáveis cupins”, de Moacyr Scliar, para responder a questão.

Havia um homem que odiava Van Gogh. Pintor desconhecido, pobre, atribuía todas suas frustrações ao artista holandês. Enquanto existirem no mundo aqueles horríveis girassóis, aquelas estrelas tumultuadas, aqueles ciprestes deformados, dizia, não poderei jamais dar vazão ao meu instinto criador.

Decidiu mover uma guerra implacável, sem quartel, às telas de Van Gogh, onde quer que estivessem. Começaria pelas mais próximas, as do Museu de Arte Moderna de São Paulo.

Seu plano era de uma simplicidade diabólica. Não faria como outros destruidores de telas que entram num museu armados de facas e atiram-se às obras, tentando destruí-las; tais insanos não apenas não conseguem seu intento, como acabam na cadeia. Não, usaria um método científico, recorrendo a aliados absolutamente insuspeitados: os cupins.

Deu-lhe muito trabalho, aquilo. Em primeiro lugar, era necessário treinar os cupins para que atacassem as telas de Van Gogh. Para isso, recorreu a uma técnica pavloviana. Reproduções das telas do artista, em tamanho natural, eram recobertas com uma solução açucarada. Dessa forma, os insetos aprenderam a diferenciar tais obras de outras.

Mediante cruzamentos sucessivos, obteve um tipo de cupim que só queria comer Van Gogh. Para ele era repulsivo, mas para os insetos era agradável, e isso era o que importava. Conseguiu introduzir os cupins no museu e ficou à espera do que aconteceria. Sua decepção, contudo, foi enorme. Em vez de atacar as obras de arte, os cupins preferiram as vigas de sustentação do prédio, feitas de madeira absolutamente vulgar. E por isso foram detectados.

O homem ficou furioso. Nem nos cupins se pode confiar, foi a sua desconsolada conclusão. É verdade que alguns insetos foram encontrados próximos a telas de Van Gogh. Mas isso não lhe serviu de consolo. Suspeitava que os sádicos cupins estivessem querendo apenas debochar dele. Cupins e Van Gogh, era tudo a mesma coisa.

(O imaginário cotidiano, 2002.)

“Enquanto existirem no mundo aqueles horríveis - UNIFESP 2020

Língua Portuguesa - 2020Leia a crônica “Inconfiáveis cupins”, de Moacyr Scliar, para responder a questão.

Havia um homem que odiava Van Gogh. Pintor desconhecido, pobre, atribuía todas suas frustrações ao artista holandês. Enquanto existirem no mundo aqueles horríveis girassóis, aquelas estrelas tumultuadas, aqueles ciprestes deformados, dizia, não poderei jamais dar vazão ao meu instinto criador.

Decidiu mover uma guerra implacável, sem quartel, às telas de Van Gogh, onde quer que estivessem. Começaria pelas mais próximas, as do Museu de Arte Moderna de São Paulo.

Seu plano era de uma simplicidade diabólica. Não faria como outros destruidores de telas que entram num museu armados de facas e atiram-se às obras, tentando destruí-las; tais insanos não apenas não conseguem seu intento, como acabam na cadeia. Não, usaria um método científico, recorrendo a aliados absolutamente insuspeitados: os cupins.

Deu-lhe muito trabalho, aquilo. Em primeiro lugar, era necessário treinar os cupins para que atacassem as telas de Van Gogh. Para isso, recorreu a uma técnica pavloviana. Reproduções das telas do artista, em tamanho natural, eram recobertas com uma solução açucarada. Dessa forma, os insetos aprenderam a diferenciar tais obras de outras.

Mediante cruzamentos sucessivos, obteve um tipo de cupim que só queria comer Van Gogh. Para ele era repulsivo, mas para os insetos era agradável, e isso era o que importava. Conseguiu introduzir os cupins no museu e ficou à espera do que aconteceria. Sua decepção, contudo, foi enorme. Em vez de atacar as obras de arte, os cupins preferiram as vigas de sustentação do prédio, feitas de madeira absolutamente vulgar. E por isso foram detectados.

O homem ficou furioso. Nem nos cupins se pode confiar, foi a sua desconsolada conclusão. É verdade que alguns insetos foram encontrados próximos a telas de Van Gogh. Mas isso não lhe serviu de consolo. Suspeitava que os sádicos cupins estivessem querendo apenas debochar dele. Cupins e Van Gogh, era tudo a mesma coisa.

(O imaginário cotidiano, 2002.)

Em “Mediante cruzamentos sucessivos, obteve um tipo de - UNIFESP 2020

Língua Portuguesa - 2020Leia a crônica “Inconfiáveis cupins”, de Moacyr Scliar, para responder a questão.

Havia um homem que odiava Van Gogh. Pintor desconhecido, pobre, atribuía todas suas frustrações ao artista holandês. Enquanto existirem no mundo aqueles horríveis girassóis, aquelas estrelas tumultuadas, aqueles ciprestes deformados, dizia, não poderei jamais dar vazão ao meu instinto criador.

Decidiu mover uma guerra implacável, sem quartel, às telas de Van Gogh, onde quer que estivessem. Começaria pelas mais próximas, as do Museu de Arte Moderna de São Paulo.

Seu plano era de uma simplicidade diabólica. Não faria como outros destruidores de telas que entram num museu armados de facas e atiram-se às obras, tentando destruí-las; tais insanos não apenas não conseguem seu intento, como acabam na cadeia. Não, usaria um método científico, recorrendo a aliados absolutamente insuspeitados: os cupins.

Deu-lhe muito trabalho, aquilo. Em primeiro lugar, era necessário treinar os cupins para que atacassem as telas de Van Gogh. Para isso, recorreu a uma técnica pavloviana. Reproduções das telas do artista, em tamanho natural, eram recobertas com uma solução açucarada. Dessa forma, os insetos aprenderam a diferenciar tais obras de outras.

Mediante cruzamentos sucessivos, obteve um tipo de cupim que só queria comer Van Gogh. Para ele era repulsivo, mas para os insetos era agradável, e isso era o que importava. Conseguiu introduzir os cupins no museu e ficou à espera do que aconteceria. Sua decepção, contudo, foi enorme. Em vez de atacar as obras de arte, os cupins preferiram as vigas de sustentação do prédio, feitas de madeira absolutamente vulgar. E por isso foram detectados.

O homem ficou furioso. Nem nos cupins se pode confiar, foi a sua desconsolada conclusão. É verdade que alguns insetos foram encontrados próximos a telas de Van Gogh. Mas isso não lhe serviu de consolo. Suspeitava que os sádicos cupins estivessem querendo apenas debochar dele. Cupins e Van Gogh, era tudo a mesma coisa.

(O imaginário cotidiano, 2002.)

No trecho “Enquanto existirem no mundo aqueles - UNIFESP 2020

Língua Portuguesa - 2020Leia a crônica “Inconfiáveis cupins”, de Moacyr Scliar, para responder a questão.

Havia um homem que odiava Van Gogh. Pintor desconhecido, pobre, atribuía todas suas frustrações ao artista holandês. Enquanto existirem no mundo aqueles horríveis girassóis, aquelas estrelas tumultuadas, aqueles ciprestes deformados, dizia, não poderei jamais dar vazão ao meu instinto criador.

Decidiu mover uma guerra implacável, sem quartel, às telas de Van Gogh, onde quer que estivessem. Começaria pelas mais próximas, as do Museu de Arte Moderna de São Paulo.

Seu plano era de uma simplicidade diabólica. Não faria como outros destruidores de telas que entram num museu armados de facas e atiram-se às obras, tentando destruí-las; tais insanos não apenas não conseguem seu intento, como acabam na cadeia. Não, usaria um método científico, recorrendo a aliados absolutamente insuspeitados: os cupins.

Deu-lhe muito trabalho, aquilo. Em primeiro lugar, era necessário treinar os cupins para que atacassem as telas de Van Gogh. Para isso, recorreu a uma técnica pavloviana. Reproduções das telas do artista, em tamanho natural, eram recobertas com uma solução açucarada. Dessa forma, os insetos aprenderam a diferenciar tais obras de outras.

Mediante cruzamentos sucessivos, obteve um tipo de cupim que só queria comer Van Gogh. Para ele era repulsivo, mas para os insetos era agradável, e isso era o que importava. Conseguiu introduzir os cupins no museu e ficou à espera do que aconteceria. Sua decepção, contudo, foi enorme. Em vez de atacar as obras de arte, os cupins preferiram as vigas de sustentação do prédio, feitas de madeira absolutamente vulgar. E por isso foram detectados.

O homem ficou furioso. Nem nos cupins se pode confiar, foi a sua desconsolada conclusão. É verdade que alguns insetos foram encontrados próximos a telas de Van Gogh. Mas isso não lhe serviu de consolo. Suspeitava que os sádicos cupins estivessem querendo apenas debochar dele. Cupins e Van Gogh, era tudo a mesma coisa.

(O imaginário cotidiano, 2002.)

O lema do carpe diem sintetiza expressivamente o motivo - UNIFESP 2020

Língua Portuguesa - 2020O lema do carpe diem sintetiza expressivamente o motivo de se aproveitar o presente, já que o futuro é incerto.

Está empregado em sentido figurado o termo sublinhado - UNIFESP 2020

Língua Portuguesa - 2020Para responder a questão, leia o trecho do livro O homem cordial, de Sérgio Buarque de Holanda.

Já se disse, numa expressão feliz, que a contribuição brasileira para a civilização será de cordialidade — daremos ao mundo o “homem cordial”. A lhaneza1 no trato, a hospitalidade, a generosidade, virtudes tão gabadas por estrangeiros que nos visitam, representam, com efeito, um traço definido do caráter brasileiro, na medida, ao menos, em que permanece ativa e fecunda a influência ancestral dos padrões de convívio humano, informados no meio rural e patriarcal. Seria engano supor que essas virtudes possam significar “boas maneiras”, civilidade. São antes de tudo expressões legítimas de um fundo emotivo extremamente rico e transbordante. Na civilidade há qualquer coisa de coercitivo — ela pode exprimir-se em mandamentos e em sentenças. Entre os japoneses, onde, como se sabe, a polidez envolve os aspectos mais ordinários do convívio social, chega a ponto de confundir-se, por vezes, com a reverência religiosa. Já houve quem notasse este fato significativo, de que as formas exteriores de veneração à divindade, no cerimonial xintoísta, não diferem essencialmente das maneiras sociais de demonstrar respeito.

Nenhum povo está mais distante dessa noção ritualista da vida do que o brasileiro. Nossa forma ordinária de convívio social é, no fundo, justamente o contrário da polidez. Ela pode iludir na aparência — e isso se explica pelo fato de a atitude polida consistir precisamente em uma espécie de mímica deliberada de manifestações que são espontâneas no “homem cordial”: é a forma natural e viva que se converteu em fórmula. Além disso a polidez é, de algum modo, organização de defesa ante a sociedade. Detém-se na parte exterior, epidérmica do indivíduo, podendo mesmo servir, quando necessário, de peça de resistência. Equivale a um disfarce que permitirá a cada qual preservar intatas sua sensibilidade e suas emoções.

Por meio de semelhante padronização das formas exteriores da cordialidade, que não precisam ser legítimas para se manifestarem, revela-se um decisivo triunfo do espírito sobre a vida. Armado dessa máscara, o indivíduo consegue manter sua supremacia ante o social. E, efetivamente, a polidez implica uma presença contínua e soberana do indivíduo.

No “homem cordial”, a vida em sociedade é, de certo modo, uma verdadeira libertação do pavor que ele sente em viver consigo mesmo, em apoiar-se sobre si próprio em todas as circunstâncias da existência. Sua maneira de expansão para com os outros reduz o indivíduo, cada vez mais, à parcela social, periférica, que no brasileiro — como bom americano — tende a ser a que mais importa. Ela é antes um viver nos outros.

(O homem cordial, 2012.)

1 lhaneza: afabilidade.

Dentre os seguintes termos empregados no primeiro - UNIFESP 2020

Língua Portuguesa - 2020Para responder a questão, leia o trecho do livro O homem cordial, de Sérgio Buarque de Holanda.

Já se disse, numa expressão feliz, que a contribuição brasileira para a civilização será de cordialidade — daremos ao mundo o “homem cordial”. A lhaneza1 no trato, a hospitalidade, a generosidade, virtudes tão gabadas por estrangeiros que nos visitam, representam, com efeito, um traço definido do caráter brasileiro, na medida, ao menos, em que permanece ativa e fecunda a influência ancestral dos padrões de convívio humano, informados no meio rural e patriarcal. Seria engano supor que essas virtudes possam significar “boas maneiras”, civilidade. São antes de tudo expressões legítimas de um fundo emotivo extremamente rico e transbordante. Na civilidade há qualquer coisa de coercitivo — ela pode exprimir-se em mandamentos e em sentenças. Entre os japoneses, onde, como se sabe, a polidez envolve os aspectos mais ordinários do convívio social, chega a ponto de confundir-se, por vezes, com a reverência religiosa. Já houve quem notasse este fato significativo, de que as formas exteriores de veneração à divindade, no cerimonial xintoísta, não diferem essencialmente das maneiras sociais de demonstrar respeito.

Nenhum povo está mais distante dessa noção ritualista da vida do que o brasileiro. Nossa forma ordinária de convívio social é, no fundo, justamente o contrário da polidez. Ela pode iludir na aparência — e isso se explica pelo fato de a atitude polida consistir precisamente em uma espécie de mímica deliberada de manifestações que são espontâneas no “homem cordial”: é a forma natural e viva que se converteu em fórmula. Além disso a polidez é, de algum modo, organização de defesa ante a sociedade. Detém-se na parte exterior, epidérmica do indivíduo, podendo mesmo servir, quando necessário, de peça de resistência. Equivale a um disfarce que permitirá a cada qual preservar intatas sua sensibilidade e suas emoções.

Por meio de semelhante padronização das formas exteriores da cordialidade, que não precisam ser legítimas para se manifestarem, revela-se um decisivo triunfo do espírito sobre a vida. Armado dessa máscara, o indivíduo consegue manter sua supremacia ante o social. E, efetivamente, a polidez implica uma presença contínua e soberana do indivíduo.

No “homem cordial”, a vida em sociedade é, de certo modo, uma verdadeira libertação do pavor que ele sente em viver consigo mesmo, em apoiar-se sobre si próprio em todas as circunstâncias da existência. Sua maneira de expansão para com os outros reduz o indivíduo, cada vez mais, à parcela social, periférica, que no brasileiro — como bom americano — tende a ser a que mais importa. Ela é antes um viver nos outros.

(O homem cordial, 2012.)

1 lhaneza: afabilidade.

Aproxima-se do argumento exposto no último parágrafo - UNIFESP 2020

Língua Portuguesa - 2020Para responder a questão, leia o trecho do livro O homem cordial, de Sérgio Buarque de Holanda.

Já se disse, numa expressão feliz, que a contribuição brasileira para a civilização será de cordialidade — daremos ao mundo o “homem cordial”. A lhaneza1 no trato, a hospitalidade, a generosidade, virtudes tão gabadas por estrangeiros que nos visitam, representam, com efeito, um traço definido do caráter brasileiro, na medida, ao menos, em que permanece ativa e fecunda a influência ancestral dos padrões de convívio humano, informados no meio rural e patriarcal. Seria engano supor que essas virtudes possam significar “boas maneiras”, civilidade. São antes de tudo expressões legítimas de um fundo emotivo extremamente rico e transbordante. Na civilidade há qualquer coisa de coercitivo — ela pode exprimir-se em mandamentos e em sentenças. Entre os japoneses, onde, como se sabe, a polidez envolve os aspectos mais ordinários do convívio social, chega a ponto de confundir-se, por vezes, com a reverência religiosa. Já houve quem notasse este fato significativo, de que as formas exteriores de veneração à divindade, no cerimonial xintoísta, não diferem essencialmente das maneiras sociais de demonstrar respeito.

Nenhum povo está mais distante dessa noção ritualista da vida do que o brasileiro. Nossa forma ordinária de convívio social é, no fundo, justamente o contrário da polidez. Ela pode iludir na aparência — e isso se explica pelo fato de a atitude polida consistir precisamente em uma espécie de mímica deliberada de manifestações que são espontâneas no “homem cordial”: é a forma natural e viva que se converteu em fórmula. Além disso a polidez é, de algum modo, organização de defesa ante a sociedade. Detém-se na parte exterior, epidérmica do indivíduo, podendo mesmo servir, quando necessário, de peça de resistência. Equivale a um disfarce que permitirá a cada qual preservar intatas sua sensibilidade e suas emoções.

Por meio de semelhante padronização das formas exteriores da cordialidade, que não precisam ser legítimas para se manifestarem, revela-se um decisivo triunfo do espírito sobre a vida. Armado dessa máscara, o indivíduo consegue manter sua supremacia ante o social. E, efetivamente, a polidez implica uma presença contínua e soberana do indivíduo.

No “homem cordial”, a vida em sociedade é, de certo modo, uma verdadeira libertação do pavor que ele sente em viver consigo mesmo, em apoiar-se sobre si próprio em todas as circunstâncias da existência. Sua maneira de expansão para com os outros reduz o indivíduo, cada vez mais, à parcela social, periférica, que no brasileiro — como bom americano — tende a ser a que mais importa. Ela é antes um viver nos outros.

(O homem cordial, 2012.)

1 lhaneza: afabilidade.

De acordo com o autor, a) a lhaneza no trato, a - UNIFESP 2020

Língua Portuguesa - 2020Para responder a questão, leia o trecho do livro O homem cordial, de Sérgio Buarque de Holanda.

Já se disse, numa expressão feliz, que a contribuição brasileira para a civilização será de cordialidade — daremos ao mundo o “homem cordial”. A lhaneza1 no trato, a hospitalidade, a generosidade, virtudes tão gabadas por estrangeiros que nos visitam, representam, com efeito, um traço definido do caráter brasileiro, na medida, ao menos, em que permanece ativa e fecunda a influência ancestral dos padrões de convívio humano, informados no meio rural e patriarcal. Seria engano supor que essas virtudes possam significar “boas maneiras”, civilidade. São antes de tudo expressões legítimas de um fundo emotivo extremamente rico e transbordante. Na civilidade há qualquer coisa de coercitivo — ela pode exprimir-se em mandamentos e em sentenças. Entre os japoneses, onde, como se sabe, a polidez envolve os aspectos mais ordinários do convívio social, chega a ponto de confundir-se, por vezes, com a reverência religiosa. Já houve quem notasse este fato significativo, de que as formas exteriores de veneração à divindade, no cerimonial xintoísta, não diferem essencialmente das maneiras sociais de demonstrar respeito.

Nenhum povo está mais distante dessa noção ritualista da vida do que o brasileiro. Nossa forma ordinária de convívio social é, no fundo, justamente o contrário da polidez. Ela pode iludir na aparência — e isso se explica pelo fato de a atitude polida consistir precisamente em uma espécie de mímica deliberada de manifestações que são espontâneas no “homem cordial”: é a forma natural e viva que se converteu em fórmula. Além disso a polidez é, de algum modo, organização de defesa ante a sociedade. Detém-se na parte exterior, epidérmica do indivíduo, podendo mesmo servir, quando necessário, de peça de resistência. Equivale a um disfarce que permitirá a cada qual preservar intatas sua sensibilidade e suas emoções.

Por meio de semelhante padronização das formas exteriores da cordialidade, que não precisam ser legítimas para se manifestarem, revela-se um decisivo triunfo do espírito sobre a vida. Armado dessa máscara, o indivíduo consegue manter sua supremacia ante o social. E, efetivamente, a polidez implica uma presença contínua e soberana do indivíduo.

No “homem cordial”, a vida em sociedade é, de certo modo, uma verdadeira libertação do pavor que ele sente em viver consigo mesmo, em apoiar-se sobre si próprio em todas as circunstâncias da existência. Sua maneira de expansão para com os outros reduz o indivíduo, cada vez mais, à parcela social, periférica, que no brasileiro — como bom americano — tende a ser a que mais importa. Ela é antes um viver nos outros.

(O homem cordial, 2012.)

1 lhaneza: afabilidade.

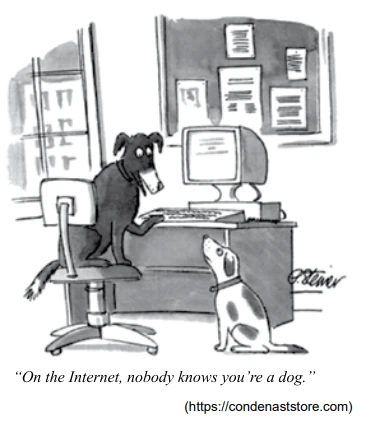

Examine o cartum de Liana Finck, publicado em sua conta - UNIFESP 2020

Inglês - 2020Examine o cartum de Liana Finck, publicado em sua conta no Instagram em 13.08.2019.

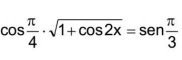

No intervalo [0, 2π], a soma de todas as soluções de - FGV 2022

Matemática - 2020No intervalo [0, 2π], a soma de todas as soluções de

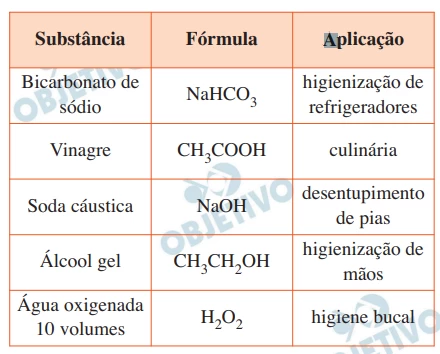

A tabela apresenta algumas substâncias químicas muito utili - FGV 2020

Química - 2020A tabela apresenta algumas substâncias químicas muito utilizadas em nosso cotidiano.

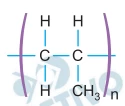

Diversos polímeros, como o polietileno, o teflon e o PVC, - FGV 2020

Química - 2020Diversos polímeros, como o polietileno, o teflon e o PVC, são produzidos pelo mesmo tipo de reação de polimerização. Esses polímeros são empregados na fabricação de embalagens e em diversas finalidades em en genharia. A fórmula estrutural de um polímero reciclável dessa classe está representada a seguir.

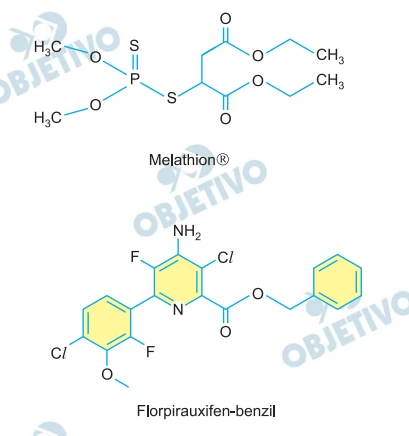

Na estrutura da molécula do florpirauxifen-benzil estão - FGV 2020

Química - 2020Entre os diversos defensivos químicos empregados na agricultura estão o Malathion® e o florpirauxifen-benzil. Suas fórmulas estruturais estão representadas a seguir.

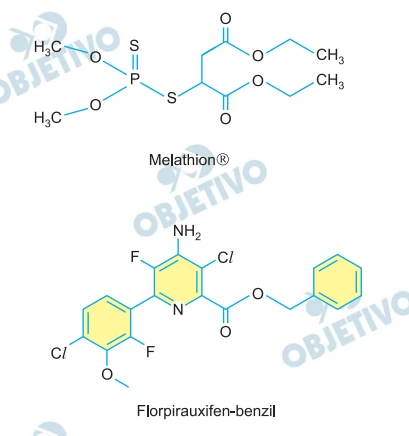

Na estrutura da molécula do Malathion®, o átomo que - FGV 2020

Química - 2020Entre os diversos defensivos químicos empregados na agricultura estão o Malathion® e o florpirauxifen-benzil. Suas fórmulas estruturais estão representadas a seguir.

Em outubro de 2017 diversos países europeus reportaram - FGV 2020

Química - 2020Em outubro de 2017 diversos países europeus reportaram detecções da presença anormal do radiosótopo rutênio-106 (106Ru) no ar atmosférico. Esse fato foi atribuído a um acidente nuclear que ocorreu na Rússia. A radioatividade referente a esse radioisótopo, medida na atmosfera, foi de 100 mBq/m3. O radioisótopo rutênio-106 decai com emissão de partículas β– com tempo de meia-vida igual a 1 ano.

Uma cozinheira preparou um molho de tomate para ser - FGV 2020

Química - 2020Uma cozinheira preparou um molho de tomate para ser consumido posteriormente, armazenando-o no refrigerador, em um recipiente de aço inoxidável coberto com uma folha de alumínio, conforme mostram as imagens.

O composto digluconato de clorexidina (DGC) possui massa - FGV 2020

Química - 2020O composto digluconato de clorexidina (DGC) possui massa molar igual a 505,5 g/mol e é o princípio ativo em soluções destinadas à assepsia e esterilização das mãos em procedimentos cirúrgicos. Uma solução alcoólica comercial desse composto contém 0,5% em massa de DGC e sua densidade é igual a 1,0 g/mL.

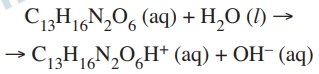

A furaltadona (C13H16N4O6) é uma substância bactericida - FGV 2020

Química - 2020A furaltadona (C13H16N4O6) é uma substância bactericida empregada no combate à salmonela, sendo adicionada à água de bebedouros em criadouros de aves. A furaltadona interage com a água de acordo com a reação representada pela equação:

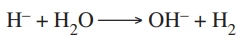

O ânion hidreto (H–) forma o hidreto de sódio (NaH), - FGV 2020

Química - 2020O ânion hidreto (H–) forma o hidreto de sódio (NaH), composto empregado no estudo do mecanismo de reações químicas, por ser um forte agente redutor. O íon hidreto reage violentamente com a água, formando o gás hidrogênio (H2), como representa a equação da reação:

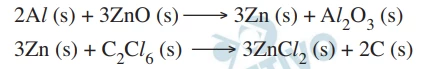

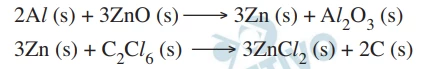

A fumaça produzida pela detonação da granada é quimicamente - FGV 2020

Química - 2020Granadas de fumaça são dispositivos usados pelas forças armadas em situações de combate, com o objetivo de ocultar a movimentação das tropas. Nesses dispositivos, os reagentes hexacloroetano (C2Cl 6), alumínio em pó (Al) e óxido de zinco (ZnO) ficam em compartimentos separados e, quando o detonador é acionado, ocorre a mistura desses reagentes, provocando uma sequência de duas reações instantâneas, representadas pelas seguintes equações:

Uma granada de fumaça contém 6 mol de cada um dos reagentes - FGV 2020

Química - 2020Granadas de fumaça são dispositivos usados pelas forças armadas em situações de combate, com o objetivo de ocultar a movimentação das tropas. Nesses dispositivos, os reagentes hexacloroetano (C2Cl 6), alumínio em pó (Al) e óxido de zinco (ZnO) ficam em compartimentos separados e, quando o detonador é acionado, ocorre a mistura desses reagentes, provocando uma sequência de duas reações instantâneas, representadas pelas seguintes equações:

O Bioglass® é um vidro que apresenta a característica de - FGV 2020

Química - 2020O Bioglass® é um vidro que apresenta a característica de se ligar fortemente ao tecido ósseo e, devido a essa propriedade, é muito empregado em implantes.

Esse material é sintetizado a partir dos seguintes óxidos: dióxido de silício, óxido de cálcio, óxido de sódio e pentóxido de difósforo.

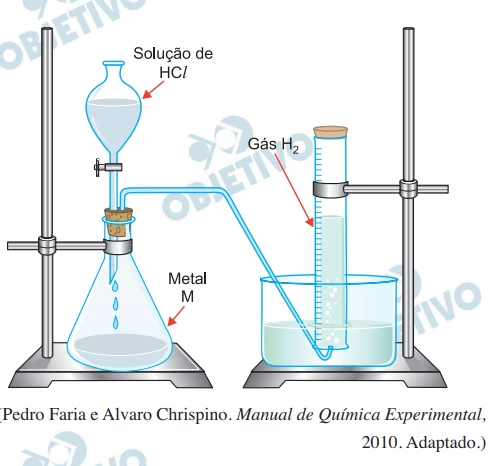

Um experimento para a identificação de um metal M foi - FGV 2020

Química - 2020Um experimento para a identificação de um metal M foi realizado de acordo com a montagem instrumental da figura.

A argentita é um minério de prata no qual o cátion - FGV 2020

Química - 2020A argentita é um minério de prata no qual o cátion monovalente do metal nobre encontra-se ligado ao ânion sulfeto.

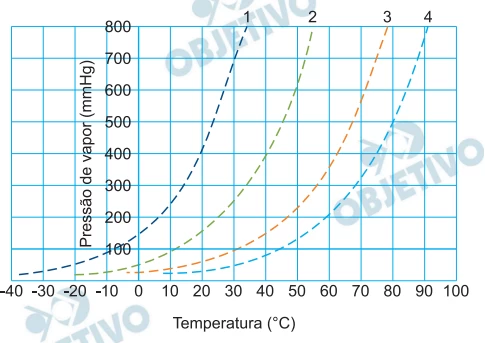

As curvas apresentadas no gráfico foram construídas com - FGV 2020

Química - 2020As curvas apresentadas no gráfico foram construídas com dados obtidos em uma pesquisa experimental que monitorou o comportamento da pressão de vapor dos líquidos 1, 2, 3 e 4 em função da temperatura.

De acordo com a teoria da relatividade de Einstein, a - FGV 2020

Física - 2020De acordo com a teoria da relatividade de Einstein, a conversão de massa em energia é regida pela expressão E = m . c2, sendo c a velocidade da luz no vácuo, que é igual a 3 × 108 m/s. No interior do Sol, ocorrem fusões nas quais quatro átomos de hidrogênio se unem para formar um átomo de hélio. A massa dos quatro átomos de hidrogênio é ligeiramente maior que a de um átomo de hélio, e essa diferença, que é de aproximadamente 5,0 × 10–29 kg, é convertida em energia.

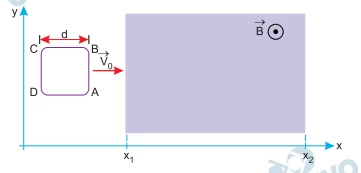

Uma espira quadrada ABCD, de lado d, move-se no plano xy, - FGV 2020

Física - 2020Uma espira quadrada ABCD, de lado d, move-se no plano xy, paralelamente ao eixo x, inicialmente com velocidade constante v0. Em dado instante, a espira entra em uma região em que existe um campo magnético uniforme, com direção perpendicular ao plano xy e sentido saindo do papel.

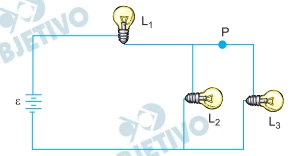

O esquema representa um circuito elétrico composto por uma - FGV 2020

Física - 2020O esquema representa um circuito elétrico composto por uma bateria ideal de força eletromotriz ε e três pequenas lâmpadas incandescentes idênticas.

A figura mostra dois instantes das configurações extremas - FGV 2020

Física - 2020A figura mostra dois instantes das configurações extremas de uma corda na qual se estabeleceu uma onda estacionária. As ondas que originam a onda estacionária têm comprimento igual a 40 cm e se propagam na corda com velocidade de 200 cm/s.

A figura mostra um raio de luz monocromática que incide na - FGV 2020

Física - 2020A figura mostra um raio de luz monocromática que incide na face AC de um prisma de vidro que se encontra mergulhado na água. A direção do raio incidente é perpendicular à face BC do prisma.

Um objeto realiza movimento harmônico simples, de amplitude - FGV 2020

Física - 2020Um objeto realiza movimento harmônico simples, de amplitude A e frequência f, em frente a um espelho esférico convexo, deslocando-se sobre o eixo principal do espelho.

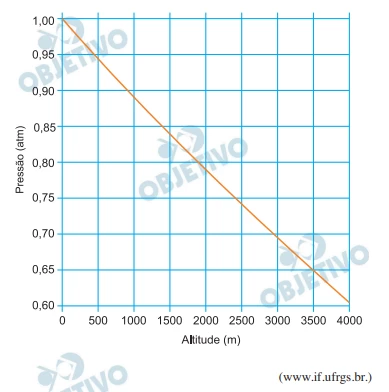

Analise o gráfico, que apresenta a variação da pressão - FGV 2020

Física - 2020Analise o gráfico, que apresenta a variação da pressão atmosférica terrestre em função da altitude.

O calor pode se propagar por meio de três processos, - FGV 2020

Física - 2020O calor pode se propagar por meio de três processos, condução, convecção e radiação, embora existam situações em que as condições do ambiente impedem a ocorrência de alguns deles.

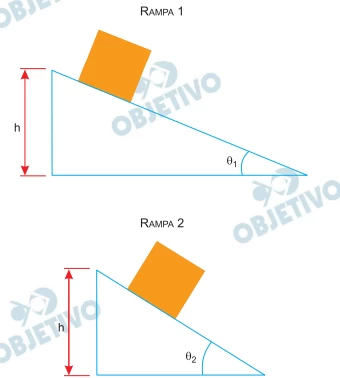

A figura mostra o mesmo bloco deslizando sobre duas rampas. - FGV 2020

Física - 2020A figura mostra o mesmo bloco deslizando sobre duas rampas. A primeira está inclinada de um ângulo 01 em relação à horizontal e a segunda está inclinada de um ângulo 02, também em relação à horizontal, sendo 01 menor que 02

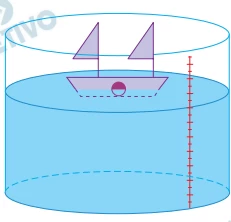

Um barquinho de brinquedo, contendo no seu interior uma - FGV 2020

Física - 2020Um barquinho de brinquedo, contendo no seu interior uma bolinha de gude de massa m, flutua na água de um recipiente, graduado em unidades de volume.

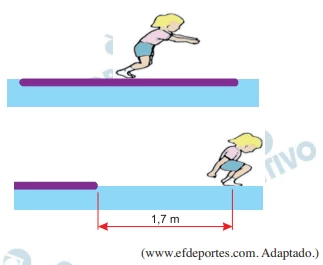

Uma criança de massa 40 kg estava em pé no centro de uma - FGV 2020

Física - 2020Uma criança de massa 40 kg estava em pé no centro de uma prancha plana, de massa 12 kg, que flutuava em repouso na superfície da água de uma piscina. Em certo instante, a criança saltou, na direção do comprimento da prancha, com velocidade horizontal constante de 0,6 m/s em relação ao solo, ficou no ar por 1,0 s e caiu na piscina a 1,7 m da extremidade da prancha.

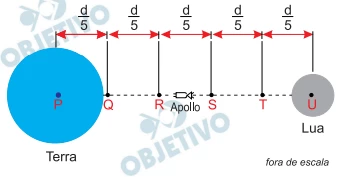

No dia 10 de junho de 1969 foi lançada a nave espacial - FGV 2020

Física - 2020No dia 10 de junho de 1969 foi lançada a nave espacial Apollo, que transportou os primeiros homens a pousarem na Lua.

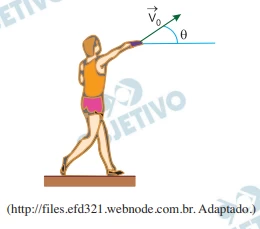

Durante uma competição, um atleta lançou um disco numa - FGV 2020

Física - 2020Durante uma competição, um atleta lançou um disco numa direção que formava um ângulo com a horizontal. Esse disco permaneceu no ar por 4,0 segundos e atingiu o solo a 60 m do ponto de lançamento.

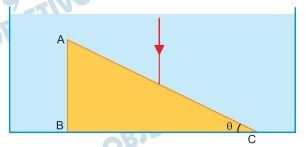

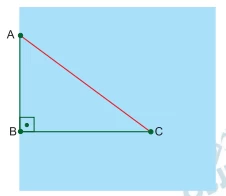

Dois amigos, Marcos e Pedro, estão às margens de um lago, - FGV 2020

Física - 2020Dois amigos, Marcos e Pedro, estão às margens de um lago, no ponto A, e decidem nadar até um barco, que se encontra no ponto C. Marcos supõe que chegará mais rápido se nadar direto do ponto A até o ponto C, enquanto Pedro supõe que seria mais rápido correr até o ponto B, que está sobre uma reta que contém o ponto C e é perpendicular à margem, e depois nadar até o barco.

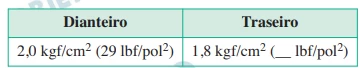

A tabela mostra os valores das pressões que devem ser - FGV 2020

Física - 2020A tabela mostra os valores das pressões que devem ser utilizadas nos pneus de um automóvel, em unidades que não pertencem ao Sistema Internacional de Unidades (SI).

O gráfico da função real f(x) = 1 + mx2 no plan - FGV 2020

Matemática - 2020O gráfico da função real f(x) = √1 + mx2

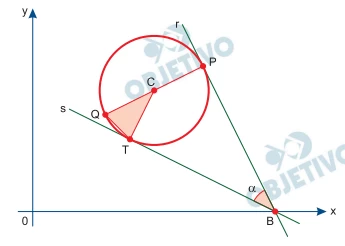

A figura indica uma circunferência de equação x2 + y2 –10x - FGV 2020

Matemática - 2020A figura indica uma circunferência de equação x2 + y2 –10x – 10y + 45 = 0, com centro em C e diâmetro PQ, no plano cartesiano de eixos ortogonais. As retas r e s se intersectam no ponto B e tangenciam a circunferência nos pontos P e T. A medida do ângulo PBT é igual a α radianos.

Um quadrado de dimensões microscópicas tem área igual a 1,6 - FGV 2020

Matemática - 2020Um quadrado de dimensões microscópicas tem área igual a 1,6 × 10–10 m2. Sendo log 2 = m e log 5 = n, a medida do lado desse quadrado, em metro,

As bandeiras dos cinco países do Mercosul serão hasteadas - FGV 2020

Matemática - 2020As bandeiras dos cinco países do Mercosul serão hasteadas em dois postes, um verde e um amarelo. As cinco bandeiras devem ser hasteadas e cada poste deve ter pelo menos uma bandeira. Constituem situações diferentes de hasteamento a troca de ordem das bandeiras em um mesmo poste e a troca das cores dos mastros associadas a cada configuração.

Ana, Bia, Cléo, Dani, Érica e Fabi se sentam ao redor de um - FGV 2020

Matemática - 2020Ana, Bia, Cléo, Dani, Érica e Fabi se sentam ao redor de uma mesa circular, como se estivessem nos vértices de um hexágono regular inscrito na circunferência da mesa. A respeito de suas posições, sabe-se que:

• Bia está imediatamente ao lado de Cléo e diametralmente oposta a Ana;

• Dani não está sentada imediatamente ao lado de Ana.

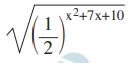

Sendo x um número real, o operador é igual a . Esse operado - FGV 2020

Matemática - 2020Sendo x um número real, o operador X é igual a Esse operador também admite composições como, por exemplo, -1 = 5. De acordo com a definição do operador, o valor de

Esse operador também admite composições como, por exemplo, -1 = 5. De acordo com a definição do operador, o valor de

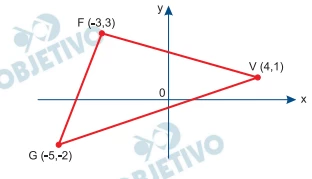

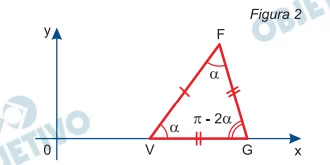

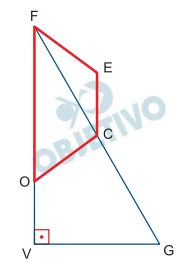

A figura indica o triângulo FGV, no plano cartesiano de - FGV 2020

Matemática - 2020A figura indica o triângulo FGV, no plano cartesiano de eixos ortogonais, e as coordenadas dos seus vértices.

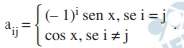

Considere a matriz quadrada A = (aij)2×2, com aij = . Sendo - FGV 2020

Matemática - 2020Considere a matriz quadrada A = (aij)2×2, com

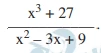

A soma das duas raízes não reais da equação algébrica x3 + - FGV 2020

Matemática - 2020A soma das duas raízes não reais da equação algébrica x3 + 2x2 + 3x + 2 = 0, resolvida em C,

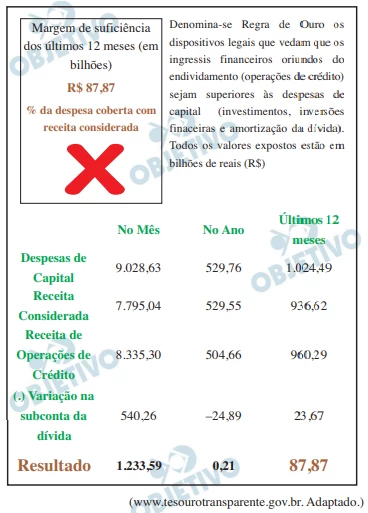

Admita que uma notícia, consultada na internet, tenha vindo - FGV 2020

Matemática - 2020Admita que uma notícia, consultada na internet, tenha vindo com um X no lugar de um gráfico, como indica a imagem a seguir

Sendo m e n números reais não nulos, um dos fatores do - FGV 2020

Matemática - 2020Sendo m e n números reais não nulos, um dos fatores do polinômio P(x) = mx2 – nx + m é (3x – 2).

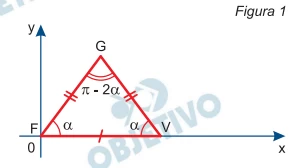

Seja FGV um triângulo isósceles, desenhado no plano - FGV 2020

Matemática - 2020Seja FGV um triângulo isósceles, desenhado no plano cartesiano de eixos ortogonais, com FG = GV = 5 e FV = 6, vértice F coincidindo com a origem dos eixos, FV contido no eixo x e ângulos internos, em radianos, como mostra a figura 1.

Uma urna contém 11 fichas idênticas, marcadas com os número - FGV 2020

Matemática - 2020Uma urna contém 11 fichas idênticas, marcadas com os números 2, 2, 3, 4, 5, 5, 5, 6, 7, 8 e 9. Retiram-se ao acaso duas fichas e denota-se o produto dos números obtidos por P. Em seguida, sem reposição, retira-se ao acaso mais uma ficha e denota-se o número obtido por N.

O valor máximo da função real dada por é igual a a) –2 - FGV 2020

Matemática - 2020O valor máximo da função real dada por

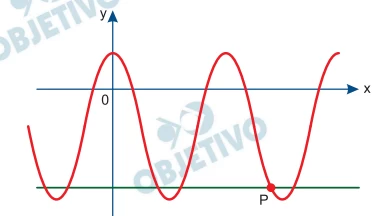

A figura indica os gráficos das funções reais definidas por - FGV 2020

Matemática - 2020A figura indica os gráficos das funções reais definidas por y = –1 + 2cos (2x) e y + 1 + √3 = 0 no plano cartesiano de eixos ortogonais, sendo P um dos pontos de intersecção dos gráficos.

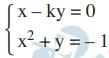

Sendo k um número real, o conjunto de todos os valores - FGV 2020

Matemática - 2020Sendo k um número real, o conjunto de todos os valores reais de k para os quais o sistema de equações

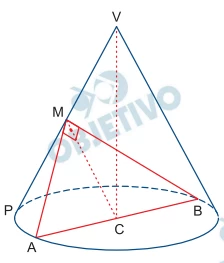

A figura indica um cone reto de revolução de vértice V, - FGV 2020

Matemática - 2020A figura indica um cone reto de revolução de vértice V, altura VC e diâmetro da base AB. O ponto M pertence à geratriz VP do cone, AMB é um triângulo de área igual a 3√3 cm2, VC = BM, CM = CA = CB = MV = MP e o ângulo A ^ MB é reto.

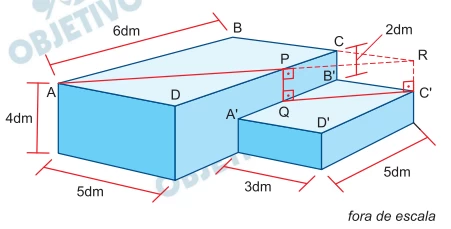

ABCD e A'B'C'D' são faces de dois paralelepípedos - FGV 2020

Matemática - 2020ABCD e A'B'C'D' são faces de dois paralelepípedos retoretangulares que estão encostados de forma que duas arestas do menor estão totalmente contidas em duas arestas do maior, como mostra a figura. Além das medidas indicadas na figura, sabe-se que:

Além das medidas indicadas na figura, sabe-se que:

• P e Q pertencem a CD e A’B’, respectivamente;

• PQ é perpendicular a A’B’;

• RCB’C’ e RPQC’ são retângulos.

Em certo dia, a cotação da libra esterlina em Nova Iorque - FGV 2020

Matemática - 2020Em certo dia, a cotação da libra esterlina em Nova Iorque era de 1,25 dólar americano por 1,00 libra, e a cotação de 1,00 dólar americano era de 4,10 reais. Nesse mesmo dia, em Londres, 1,00 libra era cotada a 5,09 reais e 1 dólar americano era cotado a 4,15 reais. Bianca e Carolina compraram, nesse mesmo dia, 415 libras cada uma.

Com a finalidade de fazer uma reserva financeira para usar - FGV 2020

Matemática - 2020Com a finalidade de fazer uma reserva financeira para usar daqui a 10 anos, Luís planejou o seguinte investimento: depositar no mês 1 a quantia de R$ 500,00 e, em cada mês subsequente, depositar uma quantia 0,4% superior ao depósito do mês anterior, em uma aplicação financeira que rende 0,5% ao mês, capitalizado mensalmente.

Para que o preço atual de um produto ficasse igual ao preço - FGV 2020

Matemática - 2020Para que o preço atual de um produto ficasse igual ao preço dele 5 anos atrás, seria necessário dar um desconto de 60%. Sabendo-se que a média entre o preço atual desse produto e o preço praticado há 5 anos é igual a R$ 168,00,

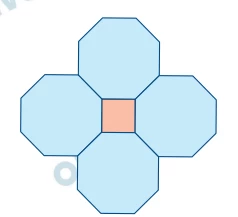

Um polígono regular de x lados está perfeitamente cercado - FGV 2020

Matemática - 2020Um polígono regular de x lados está perfeitamente cercado por polígonos regulares idênticos de y lados, sem sobreposições ou espaços livres. Por exemplo, a figura mostra a situação descrita para o caso em que x = 4 e y = 8.

Considere a equação 10z2 – 2iz – k = 0, em que z é um - FGV 2020

Matemática - 2020Considere a equação 10z2 – 2iz – k = 0, em que z é um número complexo e i2 = –1.

Uma moeda não honesta tem probabilidade igual a - FGV 2020

Matemática - 2020Uma moeda não honesta tem probabilidade igual a 2/3 de sair cara, contra 1/3 de sair coroa. Lançando-se essa moeda 20 vezes,

Na figura, FECO é um trapézio isósceles, com FE = OC = 5 cm - FGV 2020

Matemática - 2020Na figura, FECO é um trapézio isósceles, com FE = OC = 5 cm, EC = 4 cm e FO = 10 cm, e FGV é um triângulo retângulo com ângulo reto em V, com C em FG e O em FV.

Uma urna contém de bolas brancas e de bolas pretas, sendo - FGV 2020

Matemática - 2020Uma urna contém 2/3 de bolas brancas e 1/3 de bolas pretas, sendo que somente metade das bolas brancas e 2/3 das bolas pretas contêm um prêmio em seu interior. Uma bola dessa urna é sorteada aleatoriamente e, quando aberta, verifica-se que tem um prêmio no seu interior.

Uma amostra de cinco número inteiros não negativos, que - FGV 2020

Matemática - 2020Uma amostra de cinco número inteiros não negativos, que pode apresentar números repetidos, possui média igual a 10 e mediana igual a 12.

Atualmente, o preço de uma mercadoria é 20% superior ao que - FGV 2020

Matemática - 2020Atualmente, o preço de uma mercadoria é 20% superior ao que era há um ano. Sabe-se também que o preço atual é 10% superior ao preço da mercadoria na época em que ela custava R$ 100,00 a menos do que hoje.

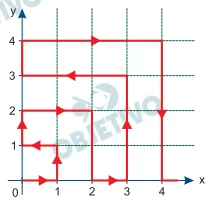

Uma formiga desloca-se sobre uma malha quadriculada com - FGV 2020

Matemática - 2020Uma formiga desloca-se sobre uma malha quadriculada com eixos cartesianos ortogonais. Ela parte do ponto de coordenadas (0, 0) e segue um caminho conforme o padrão indicado na figura.

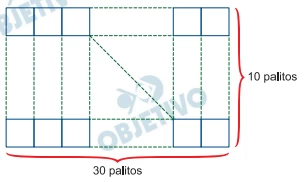

A figura indica uma configuração retangular feita com - FGV 2020

Matemática - 2020A figura indica uma configuração retangular feita com palitos idênticos.

O planeta que está ficando cada vez mais desigual. Nos - FGV 2022

Geografia - 2020O planeta que está ficando cada vez mais desigual. Nos últimos 40 anos, a concentração de renda só cresceu com a globalização. Tanto é assim que atualmente nenhum país tem maior desigualdade que a África do Sul. O país, por ironia, viu crescer a desigualdade após o fim do Apartheid.

Na oração “— Traduzo coisa nenhuma” (5.o parágrafo), o term - FGV 2020

Língua Portuguesa - 2020Leia o texto para responder

Modos de xingar

— Biltre!

— O quê?

— Biltre! Sacripanta!

— Traduz isso para português.

— Traduzo coisa nenhuma. Além do mais, charro!

Onagro!

Parei para escutar. As palavras estranhas jorravam do interior de um Ford de bigode. Quem as proferia era um senhor idoso, terno escuro, fisionomia respeitável, alterada pela indignação. Quem as recebia era um garotão de camisa esporte; dentes clarinhos emergindo da floresta capilar, no interior de um fusca. Desses casos de toda hora: o fusca bateu no Ford. Discussão. Bate-boca. O velho usava o repertório de xingamentos de seu tempo e de sua condição: professor, quem sabe? leitor de Camilo Castelo Branco.

Os velhos xingamentos. Pessoas havia que se recusavam a usar o trivial das ruas e botequins, e iam pedir a Rui Barbosa, aos mestres da língua, expressões que castigassem fortemente o adversário. Esse material seleto vinha esmaltar artigos de polêmica (polemizava-se muito nos jornais do começo do século), discursos políticos (nos intervalos do estado de sítio, é lógico) e um pouco os incidentes de calçada. A maioria, sem dúvida, não se empenhava em requintes.

(Carlos Drummond de Andrade. “Modos de xingar”.

As palavras que ninguém diz, 2011.)

A frase do último parágrafo do texto “A maioria, sem dúvida - FGV 2020

Língua Portuguesa - 2020Leia o texto para responder

Modos de xingar

— Biltre!

— O quê?

— Biltre! Sacripanta!

— Traduz isso para português.

— Traduzo coisa nenhuma. Além do mais, charro!

Onagro!

Parei para escutar. As palavras estranhas jorravam do interior de um Ford de bigode. Quem as proferia era um senhor idoso, terno escuro, fisionomia respeitável, alterada pela indignação. Quem as recebia era um garotão de camisa esporte; dentes clarinhos emergindo da floresta capilar, no interior de um fusca. Desses casos de toda hora: o fusca bateu no Ford. Discussão. Bate-boca. O velho usava o repertório de xingamentos de seu tempo e de sua condição: professor, quem sabe? leitor de Camilo Castelo Branco.

Os velhos xingamentos. Pessoas havia que se recusavam a usar o trivial das ruas e botequins, e iam pedir a Rui Barbosa, aos mestres da língua, expressões que castigassem fortemente o adversário. Esse material seleto vinha esmaltar artigos de polêmica (polemizava-se muito nos jornais do começo do século), discursos políticos (nos intervalos do estado de sítio, é lógico) e um pouco os incidentes de calçada. A maioria, sem dúvida, não se empenhava em requintes.

(Carlos Drummond de Andrade. “Modos de xingar”.

As palavras que ninguém diz, 2011.)

Analisando-se os modos de organização do texto, conclui-se - FGV 2020

Língua Portuguesa - 2020Leia o texto para responder

Modos de xingar

— Biltre!

— O quê?

— Biltre! Sacripanta!

— Traduz isso para português.

— Traduzo coisa nenhuma. Além do mais, charro!

Onagro!

Parei para escutar. As palavras estranhas jorravam do interior de um Ford de bigode. Quem as proferia era um senhor idoso, terno escuro, fisionomia respeitável, alterada pela indignação. Quem as recebia era um garotão de camisa esporte; dentes clarinhos emergindo da floresta capilar, no interior de um fusca. Desses casos de toda hora: o fusca bateu no Ford. Discussão. Bate-boca. O velho usava o repertório de xingamentos de seu tempo e de sua condição: professor, quem sabe? leitor de Camilo Castelo Branco.

Os velhos xingamentos. Pessoas havia que se recusavam a usar o trivial das ruas e botequins, e iam pedir a Rui Barbosa, aos mestres da língua, expressões que castigassem fortemente o adversário. Esse material seleto vinha esmaltar artigos de polêmica (polemizava-se muito nos jornais do começo do século), discursos políticos (nos intervalos do estado de sítio, é lógico) e um pouco os incidentes de calçada. A maioria, sem dúvida, não se empenhava em requintes.

(Carlos Drummond de Andrade. “Modos de xingar”.

As palavras que ninguém diz, 2011.)

As passagens “— O quê?” (2.o parágrafo) e “professor, quem - FGV 2020

Língua Portuguesa - 2020Leia o texto para responder

Modos de xingar

— Biltre!

— O quê?

— Biltre! Sacripanta!

— Traduz isso para português.

— Traduzo coisa nenhuma. Além do mais, charro!

Onagro!

Parei para escutar. As palavras estranhas jorravam do interior de um Ford de bigode. Quem as proferia era um senhor idoso, terno escuro, fisionomia respeitável, alterada pela indignação. Quem as recebia era um garotão de camisa esporte; dentes clarinhos emergindo da floresta capilar, no interior de um fusca. Desses casos de toda hora: o fusca bateu no Ford. Discussão. Bate-boca. O velho usava o repertório de xingamentos de seu tempo e de sua condição: professor, quem sabe? leitor de Camilo Castelo Branco.

Os velhos xingamentos. Pessoas havia que se recusavam a usar o trivial das ruas e botequins, e iam pedir a Rui Barbosa, aos mestres da língua, expressões que castigassem fortemente o adversário. Esse material seleto vinha esmaltar artigos de polêmica (polemizava-se muito nos jornais do começo do século), discursos políticos (nos intervalos do estado de sítio, é lógico) e um pouco os incidentes de calçada. A maioria, sem dúvida, não se empenhava em requintes.

(Carlos Drummond de Andrade. “Modos de xingar”.

As palavras que ninguém diz, 2011.)

Nas frases “E outra que ele come para digerir de novo” e “ - FGV 2020

Língua Portuguesa - 2020Leia a tira Níquel Náusea, de Fernando Gonsales.

Nas expressões “cientistas exasperados”, “exemplar da - FGV 2020

Língua Portuguesa - 2020Leia o texto para responder

Nos dois primeiros episódios da série Chernobyl, da HBO, cientistas exasperados tentam convencer os superiores na usina e no governo soviético de que um dos reatores nucleares explodiu e está jorrando radioatividade sobre a Europa.

A resposta dos superiores, exemplar da estupidez surrealista de uma burocracia totalitária, é sempre a mesma: impossível, um “reator RBMK não explode”. A posição oficial é que havia somente um pequeno incêndio no telhado.

“Eu fui lá, eu vi!”, repetem os cientistas, um após o outro, antes de vomitarem, verterem sangue pelos poros ou caírem duros. Apenas quando a radioatividade é detectada na Suécia, Mikhail Gorbatchov encara seus ministros com uma expressão de “camarada, deu ruim...” — naquela altura, a radioatividade liberada já era superior à de vinte bombas de Hiroshima.

Só mesmo no totalitarismo soviético, pensei, assistindo à série. Então fui ler na revista Piauí o trecho do livro A Terra inabitável: uma história do futuro, do jornalista David Wallace-Wells, que sairá pela Companhia das Letras no mês que vem. Impossível terminar as 11 páginas sobre o aquecimento global sem ficar apavorado feito um cientista em Chernobyl.

(Antonio Prata. “Bem-vindos a Chernobyl”.

www.folha.uol.com.br, 16.06.2019. Adaptado.)

Considere as passagens do texto: • [...] impossível, um - FGV 2020

Língua Portuguesa - 2020Leia o texto para responder

Nos dois primeiros episódios da série Chernobyl, da HBO, cientistas exasperados tentam convencer os superiores na usina e no governo soviético de que um dos reatores nucleares explodiu e está jorrando radioatividade sobre a Europa.

A resposta dos superiores, exemplar da estupidez surrealista de uma burocracia totalitária, é sempre a mesma: impossível, um “reator RBMK não explode”. A posição oficial é que havia somente um pequeno incêndio no telhado.

“Eu fui lá, eu vi!”, repetem os cientistas, um após o outro, antes de vomitarem, verterem sangue pelos poros ou caírem duros. Apenas quando a radioatividade é detectada na Suécia, Mikhail Gorbatchov encara seus ministros com uma expressão de “camarada, deu ruim...” — naquela altura, a radioatividade liberada já era superior à de vinte bombas de Hiroshima.

Só mesmo no totalitarismo soviético, pensei, assistindo à série. Então fui ler na revista Piauí o trecho do livro A Terra inabitável: uma história do futuro, do jornalista David Wallace-Wells, que sairá pela Companhia das Letras no mês que vem. Impossível terminar as 11 páginas sobre o aquecimento global sem ficar apavorado feito um cientista em Chernobyl.

(Antonio Prata. “Bem-vindos a Chernobyl”.

www.folha.uol.com.br, 16.06.2019. Adaptado.)

No texto, a variedade formal da língua, flagrada na - FGV 2020

Língua Portuguesa - 2020Leia o texto para responder

Nos dois primeiros episódios da série Chernobyl, da HBO, cientistas exasperados tentam convencer os superiores na usina e no governo soviético de que um dos reatores nucleares explodiu e está jorrando radioatividade sobre a Europa.

A resposta dos superiores, exemplar da estupidez surrealista de uma burocracia totalitária, é sempre a mesma: impossível, um “reator RBMK não explode”. A posição oficial é que havia somente um pequeno incêndio no telhado.

“Eu fui lá, eu vi!”, repetem os cientistas, um após o outro, antes de vomitarem, verterem sangue pelos poros ou caírem duros. Apenas quando a radioatividade é detectada na Suécia, Mikhail Gorbatchov encara seus ministros com uma expressão de “camarada, deu ruim...” — naquela altura, a radioatividade liberada já era superior à de vinte bombas de Hiroshima.

Só mesmo no totalitarismo soviético, pensei, assistindo à série. Então fui ler na revista Piauí o trecho do livro A Terra inabitável: uma história do futuro, do jornalista David Wallace-Wells, que sairá pela Companhia das Letras no mês que vem. Impossível terminar as 11 páginas sobre o aquecimento global sem ficar apavorado feito um cientista em Chernobyl.

(Antonio Prata. “Bem-vindos a Chernobyl”.

www.folha.uol.com.br, 16.06.2019. Adaptado.)

Nas passagens do texto da Exame “focos de incêndio floresta - FGV 2020

Língua Portuguesa - 2020Leia um trecho da letra da canção “Amazônia”, de Roberto Carlos, para responder

Amazônia

A lei do machado

Avalanches de desatinos

Numa ambição desmedida

Absurdos contra os destinos

De tantas fontes de vida

Quanta falta de juízo

Tolices fatais

Quem desmata, mata

Não sabe o que faz

Como dormir e sonhar

Quando a fumaça no ar

Arde nos olhos de quem pode ver

Terríveis sinais, de alerta, desperta

Pra selva viver

Amazônia, insônia do mundo

Amazônia, insônia do mundo

(www.vagalume.com.br)

Os versos “Avalanches de desatinos / Numa ambição desmedida - FGV 2020

Língua Portuguesa - 2020Leia um trecho da letra da canção “Amazônia”, de Roberto Carlos, para responder

Amazônia

A lei do machado

Avalanches de desatinos

Numa ambição desmedida

Absurdos contra os destinos

De tantas fontes de vida

Quanta falta de juízo

Tolices fatais

Quem desmata, mata

Não sabe o que faz

Como dormir e sonhar

Quando a fumaça no ar

Arde nos olhos de quem pode ver

Terríveis sinais, de alerta, desperta

Pra selva viver

Amazônia, insônia do mundo

Amazônia, insônia do mundo

(www.vagalume.com.br)

No período do quarto parágrafo “O que causa estranheza aos - FGV 2020

Língua Portuguesa - 2020Leia o texto para responder

São Paulo – Os olhos do Brasil e do mundo se voltam para a maior floresta tropical e maior reserva de biodiversidade da Terra. Milhares de mensagens de alerta em diferentes línguas circulam nas redes sociais com a hashtag #PrayForAmazonia. A razão não poderia ser pior: a Amazônia arde em chamas.

O bioma é o mais afetado pela maior onda de incêndios florestais no Brasil em sete anos. Não há novidade no fenômeno em si. A Amazônia sempre sofreu com queimadas ligadas à exploração de terra. Mas como isso chegou tão longe? Segundo dados do Inpe, o número de focos de incêndio florestal aumentou 83% entre janeiro e agosto de 2019 na comparação com o mesmo período de 2018. Desde 1.o de janeiro até a terça-feira [20.08.2019] foram contabilizados 74 155 focos, alta de 84% em relação ao mesmo período do ano passado. É o número mais alto desde que os registros começaram, em 2013. A última grande onda é de 2016, com 66 622 focos de queimadas nesse período. Combinado a períodos de seca severa, o desmatamento e a prática de queimadas podem gerar um saldo final incendiário. O que causa estranheza aos especialistas nos eventos de 2019, porém, é que a seca não se mostra tão severa como nos anos anteriores e tampouco houve eventos climáticos extremos, como o El Niño, que justifiquem um aumento considerável nos focos de incêndio. Além disso, os tempos de seca mais severos ocorrem geralmente no mês de setembro. Ou seja: a mão do homem pesou, e muito, para a alta neste ano.

(Vanessa Barbosa. “Inferno na floresta: o que sabemos sobre os

incêndios na Amazônia”. https://exame.abril.com.br, 23.08.2019.

Adaptado.)

Assinale a alternativa que atende à norma-padrão de - FGV 2020

Língua Portuguesa - 2020Leia o texto para responder

São Paulo – Os olhos do Brasil e do mundo se voltam para a maior floresta tropical e maior reserva de biodiversidade da Terra. Milhares de mensagens de alerta em diferentes línguas circulam nas redes sociais com a hashtag #PrayForAmazonia. A razão não poderia ser pior: a Amazônia arde em chamas.

O bioma é o mais afetado pela maior onda de incêndios florestais no Brasil em sete anos. Não há novidade no fenômeno em si. A Amazônia sempre sofreu com queimadas ligadas à exploração de terra. Mas como isso chegou tão longe? Segundo dados do Inpe, o número de focos de incêndio florestal aumentou 83% entre janeiro e agosto de 2019 na comparação com o mesmo período de 2018. Desde 1.o de janeiro até a terça-feira [20.08.2019] foram contabilizados 74 155 focos, alta de 84% em relação ao mesmo período do ano passado. É o número mais alto desde que os registros começaram, em 2013. A última grande onda é de 2016, com 66 622 focos de queimadas nesse período. Combinado a períodos de seca severa, o desmatamento e a prática de queimadas podem gerar um saldo final incendiário. O que causa estranheza aos especialistas nos eventos de 2019, porém, é que a seca não se mostra tão severa como nos anos anteriores e tampouco houve eventos climáticos extremos, como o El Niño, que justifiquem um aumento considerável nos focos de incêndio. Além disso, os tempos de seca mais severos ocorrem geralmente no mês de setembro. Ou seja: a mão do homem pesou, e muito, para a alta neste ano.

(Vanessa Barbosa. “Inferno na floresta: o que sabemos sobre os

incêndios na Amazônia”. https://exame.abril.com.br, 23.08.2019.

Adaptado.)